The creature was tiny, about the size and color of a grain of rice. Dan Distel, director of the Ocean Genome Legacy Center at Northeastern University in Boston, wasn’t exactly sure what it was, other than a mussel of some kind. He put the wee bivalve in a petri dish and asked a colleague to set it aside.

“By the time we got back to the lab, the little bugger had crawled out of the dish,” he recalls with some chagrin. “And we couldn’t find it.”

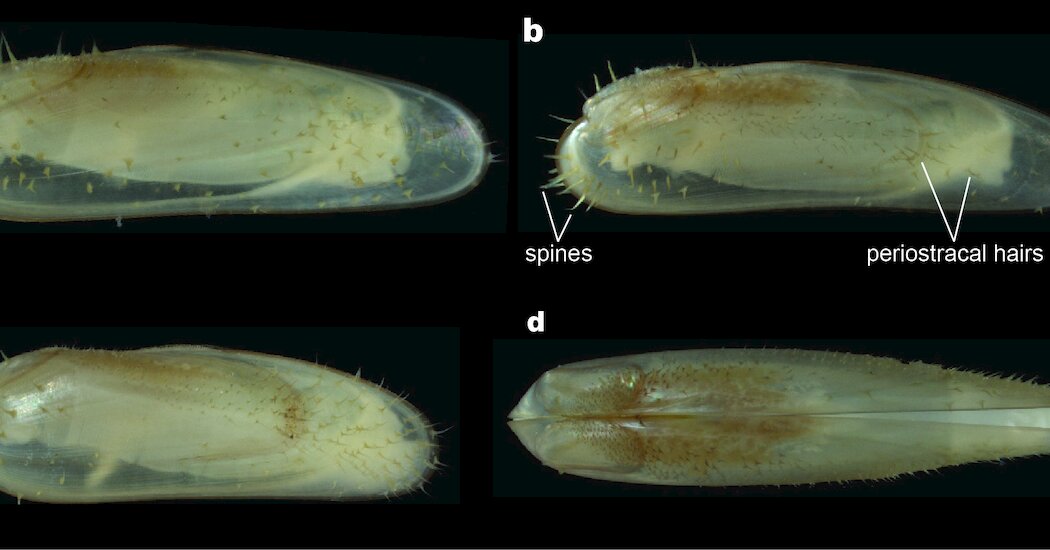

It was months later that they found another one, and Dr. Distel realized that the mussel looked oddly familiar. It resembled the giant mussels found at deep-sea hydrothermal vents 1,500 feet below the ocean’s surface, which have gills that contain bacteria that let the mussels gain nutrients from corrosive hydrogen sulfide bubbling from the Earth’s crust. But this mussel was tiny and pale and, strangest of all, lived a mere 60 feet or so down. DNA analysis soon confirmed that this mussel was a new species, which the scientists named Vadumodiolus teredinicola. It is the first mussel of this group ever seen at depths of less than 300 feet. The existence of this shallow-water cousin, the researchers suggest, could help explain how the giant mussels ended up deeper down.

Dr. Distel and his colleagues discovered the mussel while they were investigating an ancient underwater forest off the coast of Alabama. During the last ice age, bald cypresses grew in what was then a swamp a hundred miles from the ocean. Then, sometime between 45,000 and 70,000 years ago, as sea levels rose, the trees were swallowed by the advancing sea. Swirling sands wrapped the dead trees in a natural sarcophagus. For millenniums, all was still in the forest, until heavy waves stirred up by one of the hurricanes of 2004 scooped away the sand. Fishermen were startled to discover trees on the otherwise featureless bottom of the Gulf of Mexico 10 miles from dry land, and a journalist, Ben Raines, helped bring the site to scientists’ attention.

Since then, the ancient wood has provided a splendid buffet for organisms of all sorts, and Dr. Distel and his colleagues have been collecting and characterizing them as fast as they can. The wood won’t last forever, and the forest could be buried again by another big storm. But the scientists believe that this unusual environment could host organisms with unsuspected talents. Dr. Distel’s main focus is shipworms, a group of clams that tunnel through waterlogged wood, and that may be a source for new antibiotics.

These newly discovered mussels seem to live inside burrows left by dead shipworms. The 124 individuals identified in the course of the study were all found within these tunnels. They fit quite snugly, and must have crawled in when they were even smaller, Dr. Distel said.

“Once they start growing they can’t get out,” he said. “They’re stuck in there.”

That fits with how scientists suspect the mussels make their living. Like their deep-sea brethren, V. teredinicola harbor and are fed nutrients by symbiotic bacteria that require an environment with little or no oxygen. In a shipworm burrow, a mussel could plug the hole with its body, creating a low-oxygen environment for its symbionts while still accessing oxygenated ocean water it needs outside the burrow.

Another sign that points to the mussels living permanently in protective burrows is their extreme fragility.

“Their shells are paper thin,” Dr. Distel said. “To pick them up I would use a pair of paint brushes like chopsticks. If you try to pick them up with tweezers or your fingers, you’ll crush them.”

The existence of these new mussels lends credence to an older hypothesis advanced by Dr. Distel and his colleagues. In a paper published in 2000, they suggested that deep-sea mussels might have evolved from shallow-water individuals that reached the sea bottom by hitching a ride on falling pieces of waterlogged wood. At the time, there were no shallow-water mussels known to digest sulfides. But this discovery suggests that there might have been sulfide-eating mussels closer to the surface, ancestors of these new mussels and those in the deep.

There may be others as well — between 75 and 90 percent of the species suspected to live in the ocean are still undiscovered, according to the Ocean Census project. In support of this goal, Dr. Distel and his colleagues have submitted V. teredinicola to the Ocean Census. It is the first new ocean species to join the list.