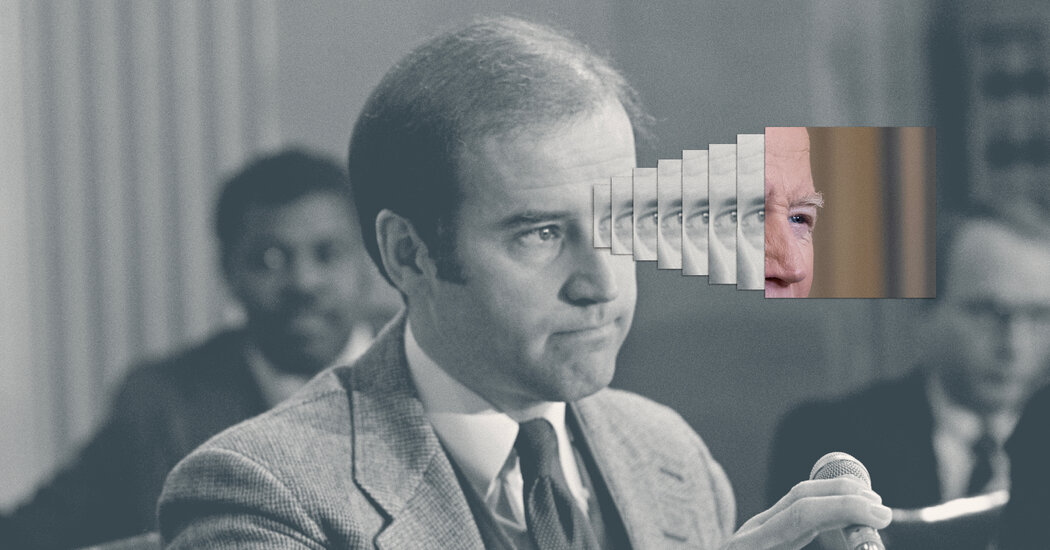

Joe Biden, you might have heard, is old. I’m sure you have thoughts about that: about his mental agility and physical stamina, about his chances for surviving a second term that is scheduled to end two months after his 86th birthday. But presidential age isn’t only a medical or actuarial matter. It has a symbolic weight, a range of cultural meanings that have so far been overlooked.

Biden is 81. Donald Trump is 77. Biden’s age has become an issue in a way that Trump’s has not, because we are being asked, as citizen-critics, to judge the president’s late style. This is what we saw at the State of the Union on Thursday night.

In criticism, to speak of a late style is to highlight the way certain artists, at the end of their careers, enter a new and distinctive phase of creativity. Sometimes they produce a succession of masterpieces that both fulfill and transcend the promise of the earlier work: Richard Wagner’s final run of operas; the three major novels Henry James published at the start of the 20th century; the movies Martin Scorsese is making now. In other cases, an older artist will revisit familiar themes with a new sense of playfulness and freedom, like Henri Matisse making cutouts, Shakespeare bending the rules of genre in “The Winter’s Tale” and “The Tempest” or Bob Dylan reshuffling the pages of his own songbook.

And then there are those artists who swerve in a more radical, dissonant direction. “The maturity of the late works,” the German theorist Theodor Adorno wrote of Ludwig van Beethoven, “does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are, for the most part, not round, but furrowed, even ravaged.” Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and last string quartets often unsettle listeners with their dissonances and their unexpected harmonies.

The literary critic Edward W. Said, who wrote the book “On Late Style,” suggested that late work like this “has the power to render disenchantment and pleasure without resolving the contradiction between them.” Clint Eastwood’s recent films (notably “The 15:17 to Paris,” “The Mule” and “Cry Macho”), at once the corniest and the most avant-garde movies in his canon, fit this description. So do Philip Roth’s bitter, incandescent final books (“Exit Ghost,” “Indignation” and “Nemesis,”), which distill the prodigious inventiveness of his great middle-period novels into austere, jagged, sometimes bluntly funny meditations on sex, death and disgrace.

What does any of this have to do with Joe Biden? Politics is not art. But it is a craft, a vocation, and not many people have practiced it as long or as devotedly as Biden. In a profile this month in The New Yorker, Evan Osnos notes that “for decades, there was a lightness about Joe Biden — a springy, mischievous energy” that is no longer in evidence. “For better and worse,” Osnos writes, “he is a more solemn figure now.”

The word “figure” is well chosen; the Biden the public thinks it knows has always been, like every other politician on the national stage, a construct, a character, a persona. That “lightness” — as well as the tendencies toward verbosity, sentimentality and handsiness that were part of Biden’s brand as senator and vice president — was a matter of style. Which isn’t to say it was inauthentic. Quite the opposite; a politician’s style, like a writer’s or an actor’s, expresses a true self as it is filtered through the discipline of performance.

Trump’s style hasn’t changed. He is manifestly the same figure he has been at least since he entered electoral politics in 2015. That may be one reason that his age seems less relevant to voters.

But Biden, during his term in office and especially in the early stages of what will be his last campaign, seems different. In Osnos’s account, the “mercurial mix of confidence and insecurity” that defined his earlier persona has given way to a “confidence that borders on serenity.”

It’s not a complete break with the past. The nine-minute journey from the door of the House chamber to the podium on Thursday night, during which the president schmoozed, kissed, mugged and took selfies, was what you might call vintage Biden, as was the self-deprecating joke that kicked off the speech.

But Americans who remember Barack Obama’s salty, smiling sidekick or the shoulder-grabbing senator from Delaware might find the solemnity and the blunt combativeness of the 46th president disconcerting. The cadence and timbre of his voice are choppier and gruffer than before, his gestures more measured, his bearing stiffer.

Thursday night’s speech echoed some often-heard themes, and hewed in its long middle section to some of the chief requirements of the genre: the listing of accomplishments, the policy promises, the shout-outs to ordinary citizens in the room. What was startling, though, was the abruptness of the tonal shifts — the quick swivels from indignation to humor, from data points to grandiloquence — and the loose, energetic way Biden handled them.

Style in politics isn’t just stagecraft and character work: It’s the politician’s way of expressing an idea, presenting an argument, embodying a set of principles and beliefs and communicating them to the public.

For most of Biden’s public career, he was a creature of the status quo and, at the same time, a proponent of abstract ideals of progress, novelty and change. In other words, he was a typical politician, perhaps the typical Democratic politician of his era. His style represented a kind of exaggerated normalcy, like Top 40 AM radio or a prime-time sitcom.

First elected to the Senate in 1972, he was part of both the school desegregation backlash and the post-Watergate reformist wave. In the late 1980s, when he started running for president, he sounded at some times like a New Democrat, tacking toward a centrist, technocratic future against the orthodoxies of the past, at others like a preacher of the old-time New Deal religion.

He was a shrewd legislator who could be clumsy and undisciplined in public, generally well liked but not always taken seriously. By 2008, his long institutional experience, his establishment credentials and his gregarious temperament made him something of an ideal vice-presidential foil for the young, cerebral Obama. In the White House, Biden served as wise man and wiseguy, contributing gravitas or comic relief as the occasion warranted.

Until the 2016 election, the vice presidency looked as if it would be the last chapter in Biden’s electoral career — as late as he would get. But then the status quo that had defined him collapsed. Top 40 AM radio is a thing of the past. Network sitcoms are not what they used to be. American politics isn’t either. In 2020, Biden ran as an agent not of change but of restoration, a man who, by virtue of his familiar face and long track record, could be counted on to bring the country back to normal after the shocks of the Trump presidency, the Covid pandemic and the racial unrest that followed the murder of George Floyd.

That didn’t happen. Biden’s late style reflects his recognition of a rupture that he finds at once undeniable and intolerable.

Said wrote that “lateness is being at the end, fully conscious, full of memory and also very (even preternaturally) aware of the present.” This is where Biden, in his final campaign, finds himself now. He insisted to his listeners, both in the room and beyond it, that “history is watching,” a phrase that summons past, present and future into a single volatile moment.

At least since Lincoln, the language of American politics — Biden’s vernacular for more than half a century — has been both nostalgic and progressive, pointing backward to a lost golden age and forward to an ever more perfect union. The most successful politicians — Reagan, Obama — have managed to bind a mythic past and an idealized future into a single prophetic story.

Biden, in his early, unsuccessful presidential campaigns, attempted to articulate a version of that story, conjuring folksy images of middle-class, midcentury Americans and vague, rosy visions of an America whose best days were yet to come. He wasn’t especially convincing.

When he revisits those tropes now it is with a sense of their fragility. He uses them to frame the argument that American liberal democracy finds itself in mortal danger. The sturdy old rhetoric of striving families and the long struggle for justice is itself imperiled, and is part of what late Biden is trying to rescue. If this election is about the survival of democracy, he has cast himself not as its savior but — for the last time — as its most plausible representative.