Klemperer was one of those conductors who sought to get out of the way of the music, to play a score objectively. It was an impulse he shared with Arturo Toscanini, whom he admired enough to say, in 1929, that “his performances are more than beautiful, they are right.” Strict, sincere, strong, Klemperer’s readings had momentum whether his tempos were glacial, as they could be near his end, or inflammatory, as they often were before that. His austerity of purpose implied no lack of intensity in execution, such that Heyworth described the effect in 1961 as one of “inspired literalness.” But the aim was impossible to fulfill, and, rather like Toscanini, Klemperer arrived at a style and sound that remains immediately audible as his.

The ideal was still there, though. Klemperer’s Bach may never have been constant, fleet and fervent and flecked with period instruments earlier in his career, then mighty and massive, even mournful later on. Yet what he once said of conducting those works applies broadly as well: “It is the interpreter’s task not to stand between them and the public, but to be the link between the two,” he wrote in The New York Times in 1942, when his career was at its nadir. “The unadorned interpretation is always the best.”

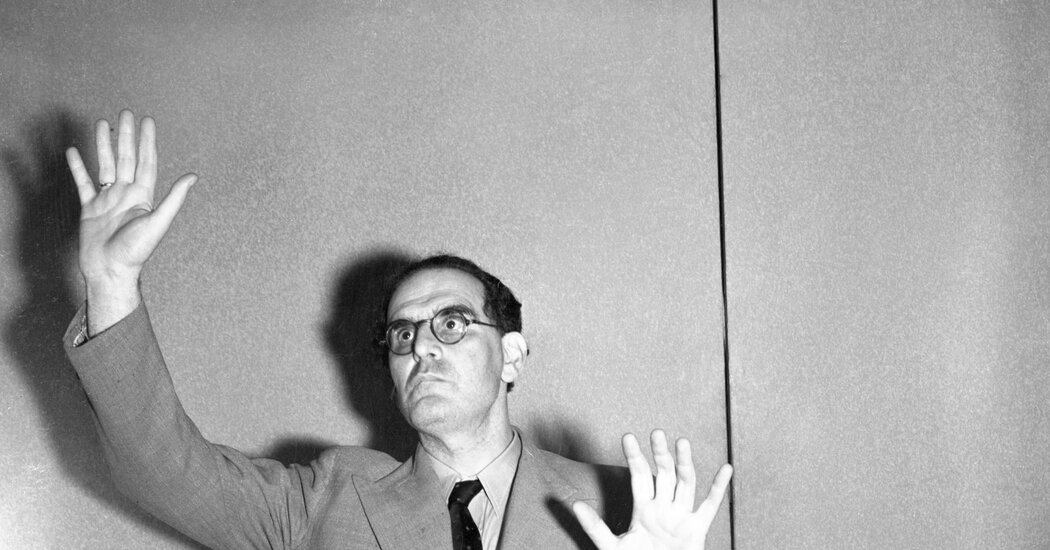

KLEMPERER WAS BORN in Breslau, Germany, in 1885, but he grew up in Hamburg. He trained in Frankfurt and Berlin, where he studied with Hans Pfitzner, spent time with Ferruccio Busoni and, in 1905, conducted the offstage band in a performance of Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony. Mahler was there, and Klemperer became obsessed with him. In 1907, Mahler scrawled a note of recommendation that promised that he was “predestined for the career of a conductor.” As Heyworth notes, Klemperer held it close until his dying day, dedicating himself to the questing ideals of the man who wrote it.

Despite suffering from manic depression, and being a terrifying presence for players and singers alike, Klemperer rose quickly through the opera houses of Central Europe, before settling in Germany: in Cologne, from 1917 to 1924, and Wiesbaden, from 1924 to 1927. He became well known for his advocacy of new music, though he had his limits; if Janacek and Stravinsky were favorites, and Hindemith and Weill later on, he could struggle with Schoenberg. And as he took charge of the Kroll — which aimed to offer a new kind of opera for the new dawn of Germany embodied in the Weimar Republic — he became known, too, for a new kind of aesthetic, the sonic corollary of the modernism that could often be discerned in designs for the house’s stage.

Klemperer had been regarded as a theatrical conductor, perhaps overly so. “Every drum beat heralded a calamity,” a Viennese critic said of his Beethoven in 1921. Some of that same volatility is evident in a Brahms First from 1928 and many of the other early recordings that are preserved on the Archiphon label, which has invaluably documented Klemperer’s activities beyond his London triumphs.