Tom Ripley’s background is always sketchy. Patricia Highsmith provides only a few rudimentary details in the first few chapters of “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” her 1955 novel that kicked off a series of five books about the elusive con artist. Tom lives in New York, in near-destitute circumstances. He has some friends — acquaintances, really — whom he hates, mentally labeling them “the riffraff, the vulgarians, the slobs.” He wants nothing more than to be rid of them, and after the first few chapters, he succeeds. He receives money from an aunt in Boston; she raised him after his parents drowned in the harbor there. He hates her, too.

When we meet Tom, he has been committing check fraud through the mail, amassing payments in the amount of $1,863.14 that he does not plan to cash. The con job was, he thinks, “no more than a practical joke, really. Good clean sport.” He’ll destroy the checks before boarding the ship that will take him to Europe, where he’s tasked with hunting down Dickie Greenleaf, the scion of a shipbuilding mogul who’s been wasting time, and money, in Italy.

The curious thing about these features of Tom Ripley’s life is that they add up to nothing. Highsmith structures them as telling details, the kinds of specifics that writers employ like shorthand to build a person in the reader’s mind. But in fact, we get very little from them, and at every turn our attempts to wrap our heads around this character are rebuffed. You might think Tom is a man of taste and talent, except he doesn’t exhibit any real taste, and the talent seems limited to a knack for forgery and impersonation. You might think he’s a malevolent mastermind seeking to bilk a wealthy family of their fortune, but he’s really just pathetic, far more concerned with making sure the Greenleafs view him as a man of their own social class. Unfortunately, he’s charmless.

Tom is not particularly handsome, clever or well-connected. He’s just miserable, but he doesn’t have much in the way of plans, or goals, beyond getting away from where he is.

This does not make Tom Ripley a screen-ready hero. He’s not even really a strong template for an antihero. But that has not stopped filmmakers from trying. Five films and now a Netflix series, starring a parade of alluring actors, have tried out various angles on the Ripley question. Who is this guy, really? A criminal? A climber? A sociopath? A thief?

Who knows? He’s a mystery, which is what makes him so primed for reinvention. A close look at the various Mr. Ripleys suggests something both confounding and fascinating: Ripley is less character than cipher, an outline of a figure onto which filmmakers (and audiences) have projected their cultural moments. Watching them all is like watching eras swing past you in living color. (And, eventually, in black and white.)

René Clément’s 1960 adaptation, “Purple Noon” (streaming on the Criterion Channel and on Kanopy; for rent on most major platforms) stars a very young Alain Delon. It’s a curious film, in that even the Americans speak and act French. (Dickie’s name is changed to Philippe.) Tom, as played by Delon, is gorgeously off-putting. He’s far more alluring than Highsmith’s version, but in an unsettling and grasping sense, as if something is not quite right upstairs. You can see the seeds of Barry Keoghan’s grifter Oliver from “Saltburn,” a vulnerable exterior concealing something more conniving beneath.

The Tom Ripley of “Purple Noon” is an existential hero, in tune with the tenor of his time, and with the novel, too — after all, the movie was released only a few years after the book’s publication. In his own strange sense, he’s self-made, the product of amoral choices that define his character, a man without wit or scruples. Held up against the book and its sequels, this seems like a perfect way to translate Tom, even if the details are transposed Frenchily. He is a character without a single essence — he’s not a born killer, not a smooth operator, not really anything in particular — who is slowly defined over the course of many books: an existential hero, in the classic Sartrean sense. It’s also why he’s so alarming and addictive. You cannot quite predict what Tom Ripley will do.

It took 17 years to see another cinematic Ripley, this time in “The American Friend” (streaming on Criterion and for rent on most major platforms). Directed by Wim Wenders, this loose adaptation of “Ripley’s Game,” the third book in Highsmith’s series, stars counterculture icon Dennis Hopper as Tom, and it’s set in Hamburg, Germany — another city Highsmith’s Ripley never lives.

Tom, now involved in an art forgery scheme, feels slighted by an upright German framer (that is, he frames art) played by Bruno Ganz. It turns into a thriller, heightened noir, a terrifically fascinating take on the character that flamboyantly emphasizes his American-ness. What’s most arresting about this Tom is the outfits Wenders puts him in. He’s shown early in New York, purchasing a massive Stetson, which he dons proudly. “Do you wear that hat in Hamburg?” a friend asks.

“What’s wrong with a cowboy in Hamburg?” he replies.

Indeed. The film’s title emphasizes that Tom is American, but so does his get-up: jeans, a denim jacket, his Marlboros, his T-shirts, his loud taste in home furnishings, and of course his hat, all of which mark him out as an American on the streets of what was West Germany. Highsmith saw the film and at first didn’t like it; later, Wenders has said, she told him that she had changed her mind, and that it “captured the essence of that Ripley character better than any other films.”

What is that essence? It’s America. Tom belongs to a postwar world where American power and wealth are fresh and abundant, but American taste varied wildly based on social class. He is the most American of archetypes, the hustler, hawking art that’s fake. He is vengeful and loyal at the same time, a man with both power and an endearing simplicity. Couple that with the fact that the film was released one year after the American bicentennial — in a time of national ennui — and Ripley’s ostentatious Americanness, which contrasts starkly with the aestheticized Europhilia of Highsmith’s character, takes on even more significance.

Both Delon and Hopper deliver midcentury takes on Ripley; by the turn of the millennium, the film business wasn’t looking for their kinds of characters. In 1999, “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” Anthony Minghella’s take on the first novel (streaming on Paramount+; for rent on most major platforms), ushered in a different type of Ripley. This version is sometimes held up as faithful to the novel, but that’s a misapprehension. Several prominent characters are completely invented. The body count is higher, too. Most important, though, Tom has undergone a transformation. He is now a relatively talented, or at least employable, pianist who is able to quickly develop an appreciation for jazz and to rub shoulders with wealthy Manhattanites. He’s pathetically needy but also goofily handsome, all teeth but, let’s face it, with the look of a movie star. (Damon was swapping in for Leonardo DiCaprio, the filmmakers’ first choice.)

In this version, Tom is also clearly gay, if closeted perhaps even to himself. There are hints in the novel that Tom may be gay, or more accurately worried about appearing gay, in a vague way that suggests he prefers not to look too hard at his own desires. (Highsmith said she didn’t think he was gay; he deploys sex only when it’s absolutely necessary to secure his station.) But the film is propelled by his desire for Dickie — to be his, to be him. Watching it, you’re reminded of what movies aimed at general audiences were like in 1999, one of the greatest years in Hollywood history. Everyone was beautiful. Everyone was very thin. And everyone seemed to be driven, primarily, by sex.

That’s even more obvious in the subsequent movies, made to capitalize on Ripley fever (and its five Oscar nominations), “Ripley’s Game” (2004) and “Ripley Under Ground” (2005). The former, directed by Liliana Cavani (and for rent on most major platforms), stars John Malkovich and treads much of the same ground as “The American Friend,” but with a very different kind of Tom. Malkovich always brings an air of the discomfiting to his roles, but his Tom is quite different from ravishing Delon or creepy Damon, and not just because he’s older. This guy is now just a seductive con artist, a genius with a knack for pulling off sophisticated deceptions and bedding beautiful women. He might freak a few people out, but only because he’s so ruthless.

This is not Highsmith’s Ripley. It’s Hollywood’s Ripley. Whereas the adaptation of “The Talented Mr. Ripley” gives Tom a healthy dose of shame and social climbing desperation, “Ripley’s Game” is about a suave monster, a cross between the hypercompetent antiheroes who would soon take over prestige television and a conscience-free serial killer.

“Ripley Under Ground” similarly features a hypercompetent Tom stripped of his weirdness. Directed by Roger Spottiswoode, it’s probably the most ludicrous of the five movies. (It’s also the hardest one to find; it’s not even rentable on digital platforms or, as far as I can tell, available on a DVD that will play in the United States.) The movie stars Barry Pepper, with flowing blond locks. He’s not good in it, but he is supposed to be not just a con man and a killer, but also a player, immensely desirable, irresistible. This is not a Tom Ripley I recognize.

The latter Ripleys reflect a Hollywood machine with a very narrow imagination. Could you even have a protagonist who wasn’t both sexually obsessed and insanely attractive? Would anyone watch a movie where the protagonist wasn’t trying to seduce beautiful people?

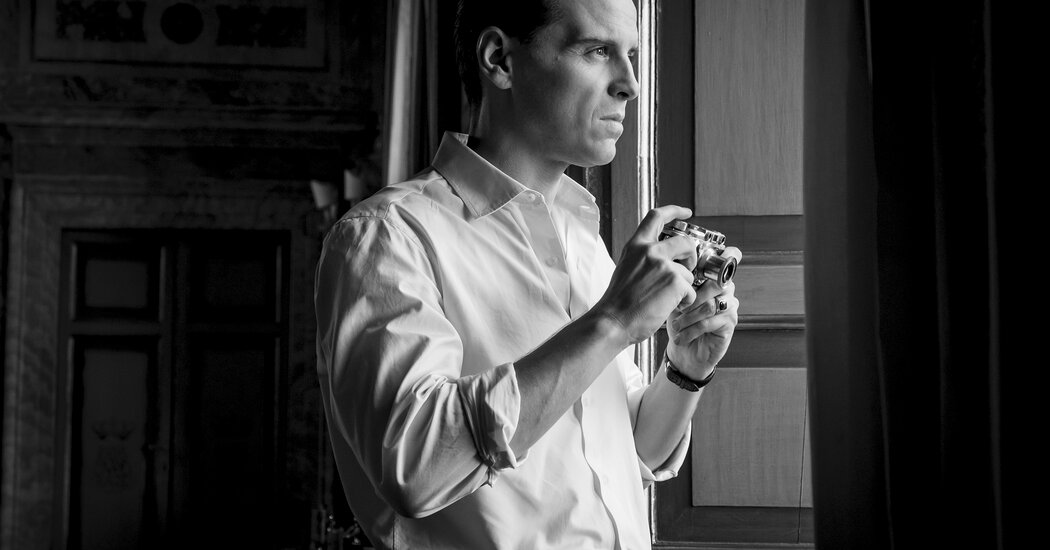

Thinking about the other Ripleys when watching the new Netflix series “Ripley,” stylishly adapted and directed by Steven Zaillian and shot by the great Robert Elswit, can provoke whiplash. It’s in black and white, the opposite of previous adaptations’ lush sensuality. Andrew Scott, who plays this Ripley, hews as closely to Highsmith’s character as I can imagine, aside from being much older (and thus, more desperate and pathetic). His face is often blank, leaving you wondering if he is great at hiding or, alternately, just has nothing to hide. Scott molds his handsomeness into ordinariness; you would never stop to look at him on the street. He seems almost simple, which is why his arc is so chilling. Perhaps a TV show was the right way to give us a window into Ripley’s strangeness all along.

But it’s not all that interesting to rank the Ripleys. Pop culture is most fascinating as a mirror reflecting us and the people who make it, and Ripley has provided unnervingly canny reflections. Highsmith’s Ripley gives a perfect blank slate onto which generations of filmmakers have projected their ideas about the world, and about what it is we want to watch. In the end, perhaps, the frightening, alluring, dangerous thing about Tom Ripley is that he is simply us.