An artist friend texted me recently, asking how to contend with the anger and sadness she was feeling about the state of the world. I can think of no better balm than the Museum of Modern Art’s Käthe Kollwitz retrospective, the first ever at a New York museum that encompasses this German artist’s groundbreaking prints and drawings and her sculpture, posters and magazine illustrations.

Once you’re there, go straight over to her series “Peasants’ War,” which she started in 1902, to find her own outlet for her burning desire for radical change. She was about 10 years into her already successful career when she made it, a remarkable feat given that she was a woman in a country that still didn’t allow women into art schools. In 1898, she had been nominated for a gold medal at the Greater Berlin Art Exhibition for her first major print cycle, “A Weavers’ Revolt” (1893-97), but did not receive it: The Prussian minister of culture thought her subject matter — a fictional uprising based on a contemporary play about an 1844 revolt, a watershed moment for many German socialists — too politically subversive, while Kaiser Wilhelm II himself objected to the idea of a woman garnering top prize.

Born in 1867, Kollwitz was an avowed socialist whose career stretched from the 1890s to the 1940s, a period of tremendous social upheaval and two world wars. Though she was a member of the progressive Berlin Secession art movement, she kept a distance from the elite art world, living in a working-class Berlin neighborhood with her husband, a doctor who tended to the poor.

With “Peasants’ War,” Kollwitz again turned to the past to share her outrage at the injustices around her “which are never ending and as large as a mountain.” The seven-part series deals with the historical revolt that swept German-speaking countries of Central Europe in the 16th century, not as a transcription of historical events but as an imagined narrative showing the exploitation of farm workers (men treated no better than animals yoked to a plow, a woman in the aftermath of a rape by a landowner), their explosive response, and the chilling repression that followed. It is a story worthy of Charles Dickens or Émile Zola, told from a woman’s point of view.

The largest print, “Charge,” focuses on the figure of “Black Anna,” reputed to be a catalyst of the violence, urging a mob of peasants to action. She is no “Liberty Leading the People.” Unlike Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 image of a beautiful and bare-breasted personification of French freedom, Kollwitz’s crone is shown from the back, her sinewy arms raised and hands clenched urgently, practically launching herself into the crowd.

It makes you want to jump on the barricades. The feminist art historian Linda Nochlin said of the series that where other artists of the time focused on addressing social issues and were intent on persuading the bourgeoisie to sympathize with the plight of the poor, Kollwitz was generating class consciousness. Her audience was, first and foremost, her working-class neighbors. It’s why she focused on making prints, which could be widely circulated, and stuck to realism even as her peers turned to more avant-garde styles (Expressionism, Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit). She wanted her message to be as accessible as possible.

But her content was only as important as her artistry. Kollwitz deployed a dizzying range of printmaking techniques in a single image: She used drypoint, different kinds of etching, and even sandpaper to mark up her metal plates in “Peasants’ War,” while in others of her series she incorporated lithography and aquatint as well; she would sometimes go in afterward with colored washes, charcoal or pastel to heighten the emotional effects of her work.

Printmaking is an oddly indirect medium — you never really know what’s going to result until you make an impression of the plate you’re marking up. This quality, combined with her almost obsessive perfectionism, means her output wasn’t huge — she made only around 275 prints in her lifetime, and around 1,500 drawings, many of which were studies for those prints. (The MoMA show, curated by Starr Figura with Maggie Hire, includes around 110 objects.)

A fascinating gallery shows the painstaking development of “Sharpening the Scythe,” the third plate of “Peasants’ War.” Over eight drawings and prints, you witness the transformation of an aged woman into a revolutionary: in the first few, a man leans over her seated figure, almost pinning her down as he shows her how to lift her weapon. In subsequent images, he disappears until, in the last iteration, she is seen sharpening the scythe, ready to take her place in the fighting. (A terrific video in this gallery walks you through Kollwitz’s process.)

It’s hard to miss the oppressiveness of the male figure in the earliest versions; that she titled them “Inspiration,” turning the man into a muse, suggests that Kollwitz felt the weight of her own artistic call to arms deeply. “I felt that I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate,” she wrote.

Kollwitz may not have been prolific by the standards of other giants of printmaking (Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, Degas), but her images are indelible. One persistent theme is that of maternal grief, born of personal circumstance (the death of her baby brother in his infancy, and her observation of her mother’s reaction to the tragedy, as well as the death of her own son later). It was borne, as well, because, in her time, infant mortality was commonplace among the poor.

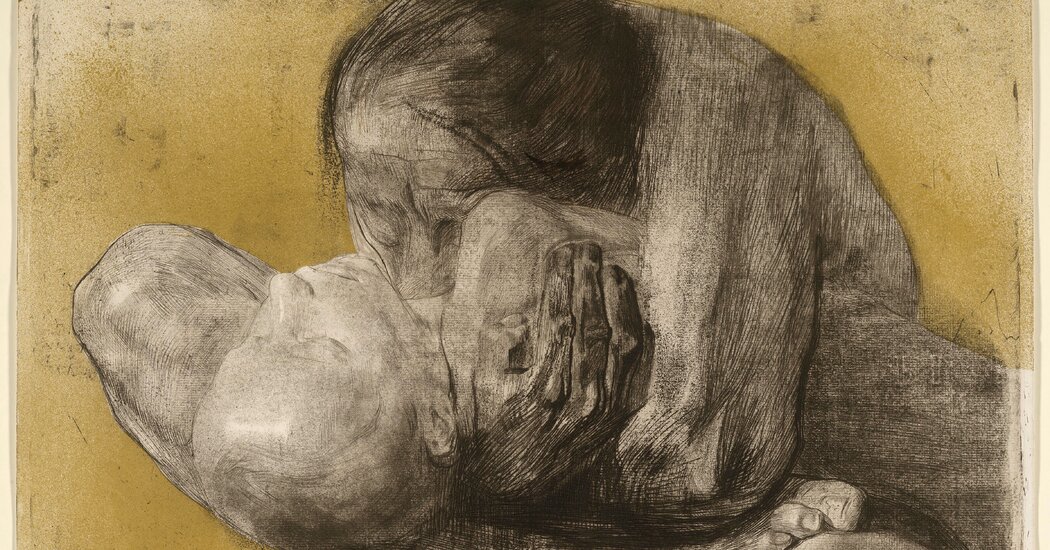

“Woman With Dead Child,” from 1903, depicts a mother embracing her child so tightly their bodies become one; the curators have managed to gather six artist’s proofs — test runs, in effect, in which Kollwitz experiments with color and other effects. (Her equally gutting series, “Pietà,” from the same year, focuses on a father’s mourning.) In these and other explorations of the theme, she paradoxically draws from erotic imagery — by Edvard Munch, Auguste Rodin, even Constantin Brancusi — to show the rawness of parental suffering.

When her younger son Peter died on the front lines of the Great War only months after it began in 1914, Kollwitz was stricken with a grief so profound that it changed the political direction of her work; she felt guilty for allowing him, still underage, to enlist. The triumphant proletarian crowds dancing around the guillotine in “The Carmagnole” (1901) gave way to an equally fervent pacifism, with women as protectors from violence rather than instigators of revolt. In her series “War” (1921-22), she turned to woodcuts — popularized years before by the German Expressionist artists — to convey the horrors of the home front. One sheet in the portfolio — “The Mothers” — shows women huddled around their children with locked arms, a solid mass; in the 1930s, she would translate this group into a bronze sculpture (“Tower of Mothers”).

Against the backdrop of the 1918 November Revolution which saw the establishment of the Weimar Republic the following year, Kollwitz turned to the quicker and more expressive medium of lithography for posters that addressed everything from the release of German prisoners of war to food shortages to legalizing abortion. Her most famous, “Never Again War!” (1924), was reproduced widely in leftist publications, turning her into an icon of socially engaged art.

Though she declared herself long past the age of believing that revolution was worth the price of violence, it didn’t stop her from making a print marking the funeral of Karl Liebknecht, a Communist leader who, with the socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, was killed for his role in an armed revolt in Berlin in 1919. Kollwitz didn’t have to agree with him politically to understand what his loss meant to his working-class followers, whose faces she focuses on in her rendering.

Her increasing fame both in Germany and abroad led to her being the first woman admitted to the Prussian Academy in 1919, but it also resulted in her persecution by the Nazis in the years leading up to World War II. After Hitler became chancellor in 1933, she was forced to resign from teaching for having signed petitions opposing the Nazi party. Two years later, her work was declared “degenerate,” and she was threatened with confinement in a concentration camp. Unlike so many of her peers, however, she never left the country; she lost her husband in 1940 and her grandson on the battlefield two years later, and she died in 1945.

Since then, her reputation has ebbed and flowed — thanks to her focus on printmaking (often considered a lesser art compared to painting and sculpture), her style (too close to Soviet Socialist realism for Cold War tastes), and her attention to women’s experience (too “sentimental” for American critics of the 1950s and ’60s). Yet she remained a fixture of feminist histories of modern art, and, as I discovered thanks to an excellent essay by Sarah Rapoport in the show’s handsome catalog, had a profound influence on African American artists fighting for social change, including Jacob Lawrence, Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett, who channeled “Black Anna” in her 1946 linocut of Harriet Tubman leading the enslaved to freedom.

Kollwitz’s harrowing final print series, “Death” (1934-37), is defiantly, if subtly, political. She had turned to lithography, which allowed her to make emphatic, sweeping strokes quickly on the stone, as close to painting as printmaking can come. In the final plate, which has the air of a self-portrait, she is sanguine as Death’s hand reaches out to her. Whatever there is to fear about one’s own demise, she seems to say, it couldn’t be worse than the evils of the world she was living in already.

Käthe Kollwitz

Member previews Thursday-Saturday; opens Sunday—July 20, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, Manhattan, (212) 708-9400; moma.org.