Richard Gambino, the chairman of the first academic Italian American studies program in the United States and a leading critic of those who reflexively viewed Italian Americans as Mafiosi and mocked them with ethnic stereotypes in popular culture, died on Jan. 12 at his home in Southampton, N.Y. He was 84.

His death, in hospice care, was caused by lymphoma, his daughter Erica-Lynn Huberty said.

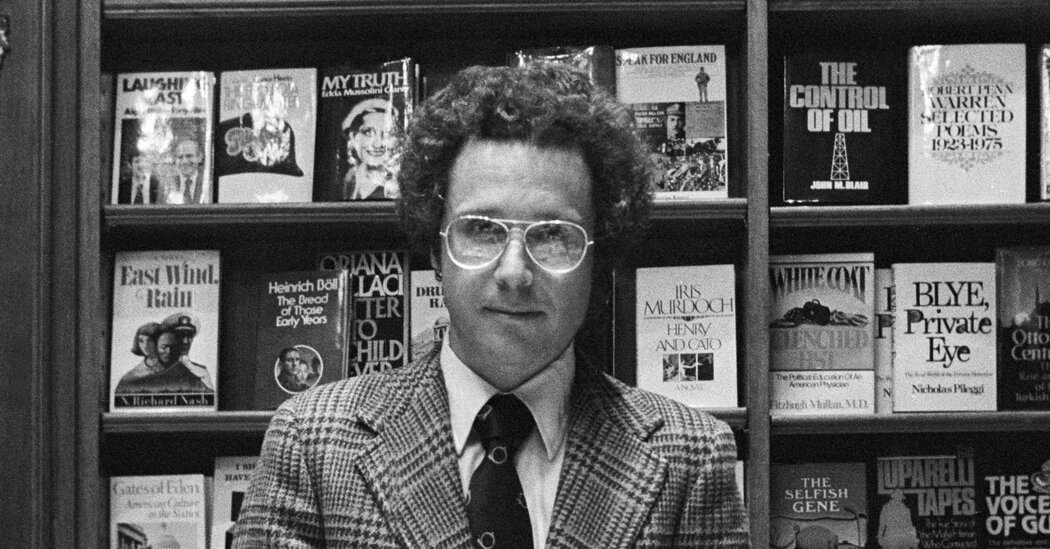

Dr. Gambino was an assistant professor of educational philosophy at Queens College in 1972 when he published a lengthy essay about Italian Americans in The New York Times Magazine, one month after the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s movie “The Godfather.”

He wrote that the “nativistic American mentality, born of ignorance and nurtured by malice,” insisted on stereotypes of Italian Americans as either “spaghetti-twirling, opera-bellowing buffoons in undershirts (as in the TV commercial with its famous line, ‘That’sa spicy meatball’), or swarthy, sinister hoods in garish suits, shirts and ties.”

He added, “The incredible exploitation of ‘The Godfather’ testifies to the power of the Mafia myth today.”

The Mafia myth — which suggested that a significant percentage of Italian Americans were involved with, or benefited from, organized crime — occupied Dr. Gambino in the decades after he was named to lead the newly formed Italian American studies program at Queens College in 1973. It was also one of several subjects covered in his well-received book “Blood of My Blood” (1974), a personal, sociological and psychological exploration of his ethnic group’s first, second and third generations.

“The Mafia image of Italian Americans is an older one than is commonly understood,” he wrote in “Blood of My Blood.” “It has been a cross laid across the shoulders of every Italian American for upwards of a full century.”

Ms. Huberty said that her father had conversations with Mario Puzo, the author of “The Godfather,” the 1969 blockbuster novel that was the basis for the movie, about his motivations for writing it.

Mr. Puzo “told him he knew that he would make money writing about the Mafia,” Ms. Huberty said in a phone interview. “My dad wasn’t particularly happy about it, but understood it. He had a similar problem with David Chase, with ‘The Sopranos.’ He wouldn’t watch it.”

Richard Ignatius Gambino was born on May 5, 1939, in Brooklyn. His father, Dominick, an immigrant from Palermo, Sicily, was a meter checker for Con Edison. His mother, Catherine (Tranchina) Gambino, a first-generation Italian American, worked in a shoulder-pad factory and then as a bookkeeper.

While attending Queens College in the late 1950s and early ’60s, he watched “The Untouchables,” the television series starring Robert Stack as Eliot Ness, the Prohibition agent who battled organized crime in Chicago in the 1930s. He noticed that many of the criminals’ names were Italian.

“I remember having to clench my teeth in anger and humiliation when I heard some students casually refer to the program” using a slur for Italians, he wrote in “Blood of My Blood.” He wanted to fight them, but, feeling isolated on a campus with few Italian Americans, he did not.

He graduated from Queens College in 1961 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy. He then earned two more philosophy degrees: a master’s from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1965 and a Ph.D. from New York University in 1968.

He was hired by the New York Society for Ethical Culture in Manhattan as a leader and teacher of adult education in 1965. He moved to Queens College two years later.

Dr. Gambino directed the Italian American studies program — an interdisciplinary minor with courses in history, political science, psychology, literature, art and music — for more than 20 years.

“He brought Italian American studies into the broader public,” Anthony Julian Tamburri, dean of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, also at Queens College, said by phone. “It was a way to get more working-class Italian American and foreign Italian students into class to show them the real history of Italian Americans.”

Early in his tenure, Dr. Gambino was faced with overt discrimination based on his heritage. After a neighbor was killed, he told United Press International in 1974, a police detective questioned him about what he assumed were his Mafia relationships.

That year, he founded the journal Italian Americana. He continued to write throughout his academic career, and he was also widely quoted in articles arguing for the broadening of cultural views of his ethnic group.

In his book “Vendetta” (1977), he wrote about the killings of 11 Italian Americans — two of them were shot, nine were hanged — by a rampaging mob in New Orleans in 1891 after a jury failed to convict a group of Italian Americans for the shooting death of David Hennessy, the city’s police chief. In his last words, Chief Hennessy was said to have blamed Italian Americans for attacking him, using an ethnic slur.

“There was no evidence that those men or any Italian Americans were responsible for Hennessy’s murder,” Dr. Gambino told The Daily News of New York in 1977. He called the incident “the largest lynching in American history.”

In “Vendetta,” Dr. Gambino took note of the enduring bias against Italian Americans. He quoted President Richard M. Nixon telling one of his aides, John Ehrlichman, in a 1973 White House tape: “They’re not like us. Difference is they smell different, they look different, act different.”

“Vendetta” was adapted into an HBO movie in 1999 starring Christopher Walken as James Houston, a leader of the lynch mob, and Clancy Brown as Chief Hennessy.

Dr. Gambino also wrote plays — “Camerado,” about Walt Whitman, and “The Trial of Pope Pius XII” — that were staged in the early 2000s on Long Island.

He Gambino left Queens College in 1998. He also taught at Stony Brook University as a visiting professor in European languages from 1994 to 1997.

In addition to Ms. Huberty, Mr. Gambino is survived by his wife, Gail (Cherne) Gambino, whom he married in 1971 and whose father, Leo Cherne, was the chairman of the International Rescue Committee; another daughter, Doria Gambino; a son, Mark; a stepdaughter, Lisa Beatty; and two grandchildren. His marriage to Barbara Barnett ended in divorce.

Dr. Gambino stayed alert his entire adult life to incidents of prejudice against Italian Americans.

In 1993, he criticized Jack Weinstein, a federal district judge, for saying during the sentencing of a mob boss that “there is a large part of the young Italo-American community that should be discouraged” from going into crime.

“This is more than an instance of a thoughtless, insensitive remark,” Dr. Gambino wrote in New York Newsday; it is “one more confirmation of what has been called by investigative journalist Jack Newfield ‘the most tolerated intolerance’ in the United States today: anti-Italian prejudice.”