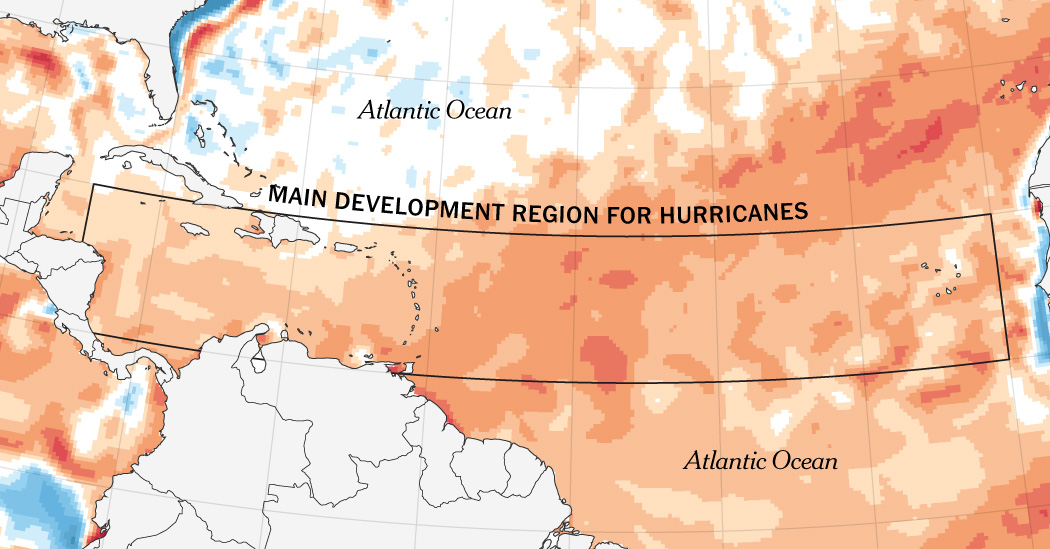

A key area of the Atlantic Ocean where hurricanes form is already abnormally warm, much warmer than an ideal swimming pool temperature of about 80 degrees and on the cusp of feeling more like warm bathtub water.

These conditions were described by Benjamin Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami, as “unprecedented,” “alarming” and an “out-of-bounds anomaly.” Combined with the rapidly subsiding El Niño weather pattern, it is leading to mounting confidence among forecasting experts that there will be an exceptionally high number of storms this hurricane season.

One such expert, Phil Klotzbach, a researcher at Colorado State University, said in his team’s annual forecast on Thursday that they expected a remarkably busy season of 23 named storms, including 11 hurricanes — five of them potentially reaching major status, meaning Category 3 or higher. In a typical season, there are 14 named storms with seven hurricanes and three of them major.

Dr. Klotzbach said there was a “well above-average probability” that at least one major hurricane would make landfall along the United States and in the Caribbean.

It’s the Colorado State researchers’ biggest April prediction ever, by a healthy margin, said Dr. Klotzbach. While things could still play out differently, he said he was more confident than he normally would be this early in the year. All the conditions that he and other researchers look at to forecast the season, such as weather patterns, sea surface temperatures and computer model data, are pointing in one direction.

“Normally, I wouldn’t go nearly this high,” he said, but with the data he’s seeing, “Why hedge?”

If anything, he said, his numbers are on the conservative side, and there are computer models that indicate even more storms on the way.

The United States was lucky in 2023.

Last year was unusual. Though only one hurricane, Idalia, made landfall in the United States, 20 storms formed, a number far above average and the fourth most since record keeping began.

Typically, the El Niño pattern that was in force would have suppressed hurricanes and reduced the number of storms in a season. But in 2023, the warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic blunted El Niño’s effect to thwart storms.

That left Idalia as the one impactful storm of the season in the Atlantic, with 12 deaths attributed to it and over $1 billion in damage. It hit in the big bend of Florida, where few people live, and the prevailing thought among hurricane researchers is that the East Coast got lucky, Dr. Klotzbach said.

That luck may change this year.

The El Niño pattern is dwindling now, and the likelihood of a La Niña pattern emerging during the hurricane season could also cause a shift in the steering pattern over the Atlantic. During an El Niño weather pattern, the area of high pressure over the Atlantic tends to weaken, which allows for storms to curve north and then east away from land. That’s what kept most of the storms last year away from land.

A La Niña weather pattern would already have forecasters looking toward an above-average year. The possibility of a La Niña, combined with record sea surface temperatures this hurricane season, could create a robust environment for storms to form and intensify this year.

Just because there are strong signals during an El Niño year that one thing will occur, it doesn’t mean the opposite happens during a La Niña year, Dr. Kirtman said. But if the high pressure strengthens and shifts west, it would mean more hurricanes making landfall.

The region where storms are most likely to form is often called the “tropical Atlantic,” stretching from West Africa to Central America and between Cuba and South America. During a La Niña year, Dr. Klotzbach said, there’s a slight increase in hurricanes forming in the western side of this main development zone — closer to the Caribbean than to Africa. When a storm forms there, it is more likely to make landfall because it’s closer to land.

And while it is difficult to predict specific landfalls this far ahead of the season, the sheer odds of more storms increases the expected risk to coastal areas.

Sea surface temperatures also affect the hurricane season. Over the past century, those temperatures have increased gradually. But last year, with an intensity that unnerved climate scientists, the warming ratcheted up more rapidly. And in the main area where hurricanes form, 2024 is already the warmest in a decade.

“Crazy” is how Dr. Kirtman described it. “The main development region is, right now, warmer than it’s historically been,” he said. “So it’s an out-of-bounds anomaly.”

There is little doubt in his mind that we are seeing some profound climate change impacts, but scientists don’t know exactly why it is occurring so quickly all of a sudden.

But it is happening, and it is likely to affect the season.

“The chances of a big, big hurricane that has a large impact making landfall is definitely increased,” he said.

Early forecasts aren’t always right.

It’s reasonable to take this forecast with a grain of sea salt; the seasonal forecast in April hasn’t always been the most accurate.

Colorado State University’s April forecast for the 2023 hurricane season called for a slightly below-average season with 13 named storms. Instead, there were 20. Even Dr. Klotzbach admits the April forecast isn’t always the best prediction, but its accuracy is improving.

The weather can be fickle, and much can change before the season officially begins on June 1. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will issue its own forecast in late May.

But for now, Colorado State and a few other forecasting groups have all called for one of the busiest seasons on record.

By year’s end, Dr. Klotzbach said, he’ll be writing a scientific paper on one of two things: the incredibly active hurricane season of 2024, or one of the biggest head fakes in Atlantic hurricane season history. But he’s pretty confident it will be the former. “If it turns out to be two hurricanes,” he said, “then I should just quit and do something else.”