In 1929 in Savannah, Ga., Edna Sutton dreamt of being a nurse.

But, as a young black woman, she had few opportunities in her hometown, which was still ruled by Jim Crow laws.

The only nursing she could do was visiting the Negro settlements on the outskirts of the city, administering whatever homespun help she could to ailing patients in clapboard shacks.

So, she headed to New York, where there was a widespread nurse shortage.

Amidst the tuberculosis epidemic, young white women were leaving the field in droves for less dangerous opportunities.

The city recruited young black women from the Deep South to fill the void.

They were offered a salary, free housing and paid tuition to one of the city’s two black nursing schools in exchange for work in the city’s hospital wards — especially the most dangerous ones, like Sea View Sanatorium on Staten Island.

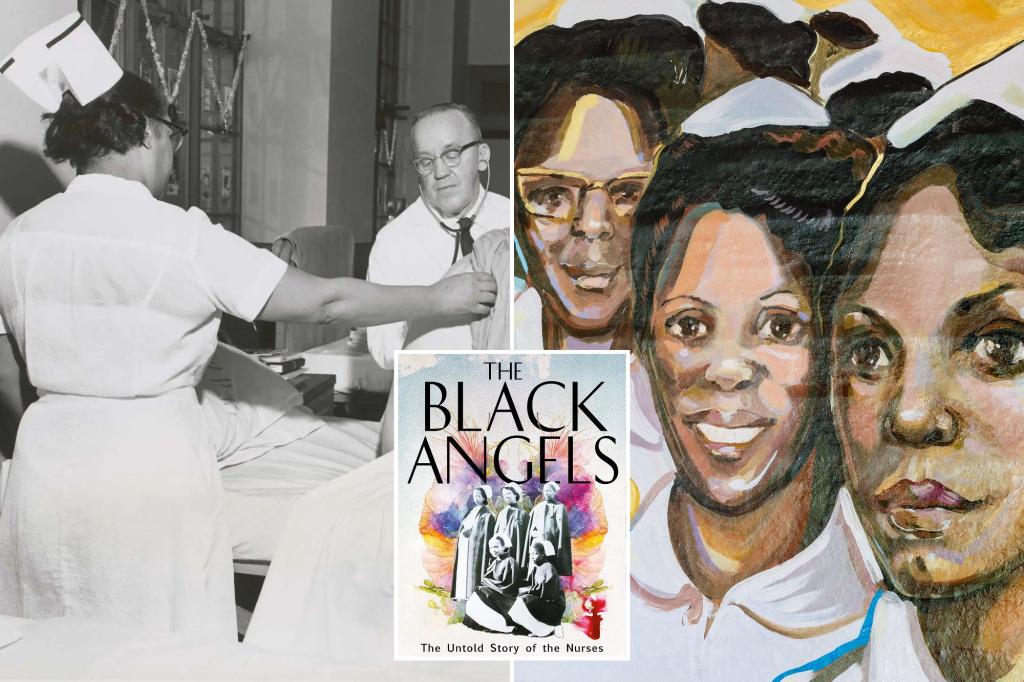

“The black nurses ran the wards,” long-time Sea View director Dr. Edward Robitzek says in Maria Smilios’s new book “The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis” (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, out now). “They helped cure tuberculosis and close down this hospital.”

The book portrays the challenges the black nurses faced caring for the hospital’s gravely ill patients while being ostracized by State Island’s white residents — and how they ultimately helped to end the epidemic.

In the early 1900s, New York City was decimated by tuberculosis.

The Lower East Side was called “the locus of disease.”

Its roughly 2 million immigrants were jammed into cramped tenements on blocks nicknamed “The Morgue” or “Lung Alley,” which the writer Jacob Riis called “fever-breeding structures.”

The city historically quarantined its ailing – in places like the Blind Asylum, the New York City Lunatic Asylum, the Idiot Asylum, the Hospital for Incurables and the Smallpox Hospital – and did the same for the highly-contagious “lungers” or “consumptives” stricken with TB.

Sea View was the city’s largest sanatorium, opened in 1913 to keep those infected away from the general population.

It worked, with the city’s death rate from TB dropping from 10% to 5% by 1920.

Sutton was one of the first black nurses at Sea View.

She and her colleagues were grateful for the chance for full-time nursing work, but they still found Sea View a forlorn place.

With no cure for TB, the hopeless patients taking the “rest cure” could do nothing but sit and suffer.

“They sweated and groaned and cried out; they coughed and choked and spit up blood, each hack sending swarms of live germs on to bedpans and sheets . . . walls and nightstands,” Smilios writes.

The TB patients had to contend with boredom and isolation, bad food and violence, leading many Sea View residents to depression and suicide.

Death was a constant, with the patients themselves making macabre wagers about who would be called next by “the Bone Man.”

“No one ever recovers at Sea View,” Smilios quotes one hospital administrator as saying. “We are in the business of dying,” another agreed.

The black nurses did what they could to ease the suffering, bathing and shaving the patients, cleaning and wiping them, emptying bedpans.

They took urine and sputum samples, logged temperatures and pulses, doing all they could to keep the patients comfortable and the doctors informed.

They were heavily involved in administering treatments, too, whether experimental drugs or experimental surgeries.

Sutton became a surgical nurse, assisting doctors in the brutal operations they hoped might ease patients’ suffering, including pneumothorax surgery (piercing the lung with a long needle) and thoracoplasty (hacking off a piece of the lung).

If those surgeries went wrong, however, doctors too frequently blamed Sutton and her colleagues, calling the black nurses “saboteurs” or “slovens.”

They suffered other indignities.

Black nurses were discouraged from buying homes on Staten Island (“not on my block” was the local rallying cry), threatened with letters from the KKK and at least one burning cross.

In 1942 a Nazi prisoner-of-war housed at Sea View told the nurse who cared for him for over a year that he “hated n—-rs,” then spit on her and saying “he hoped she would get sick.”

Meanwhile, no black nurse was given a promotion or salary increase for the first three years Sutton worked there. Many were infected with tuberculosis themselves and were forced to work without masks or gowns.

When it was time in the mid-1950s to do a massive, human trial on a new drug that might cure TB called isoniazid, researcher Herbert Fox of the Hoffman-LaRoche company needed many patients of diverse backgrounds with different variations of the disease.

He found all that at Sea View and thus chose it to host his trial, in large part also because of the extensive experience of Edna Sutton and her black co-workers.

“No one was more qualified than these nurses to assist . . . with a trial of this magnitude,” Smilios writes.

Isoniazid proved to be a highly effective tool to fight the disease.

“Alone and in combination with other drugs . . . [isoniazid] was not only safe but almost 95% effective at ensuring a patient’s survival,” Smilios writes.

Today, tuberculosis has not been entirely eradicated from Earth, but isoniazid has greatly reduced its effects. Since 2000, it’s estimated the drug therapy has saved some 66 million lives around the world.

As for those “Black Angels,” Sea View’s nurses were so helpful in treating TB patients and returning them safely home that in 1961 the facility was closed.

“Ironically,” Smilios writes, those women “had probably worked themselves out of a job.”