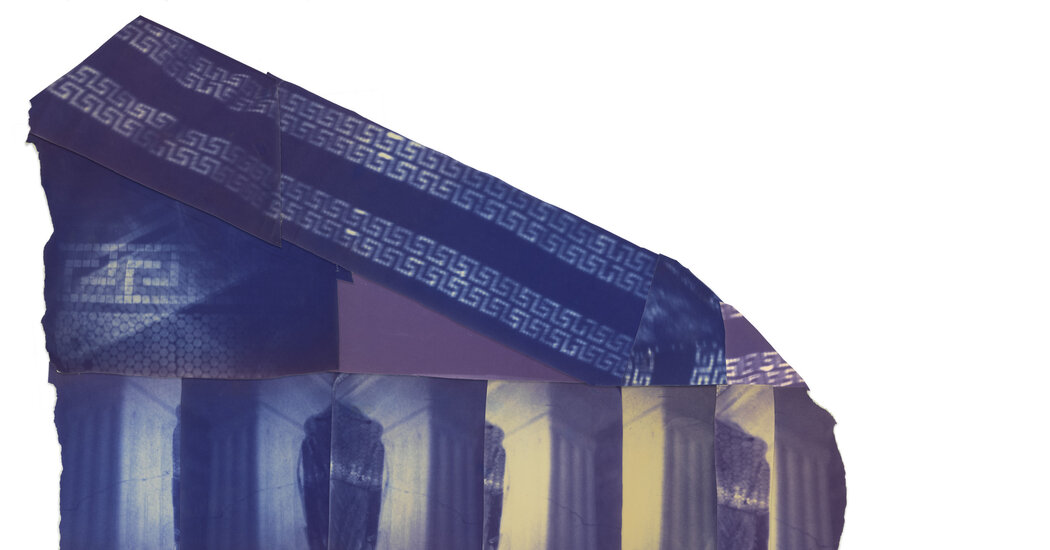

In the year before she jumped to her death in January 1981, Francesca Woodman toiled furiously on her most ambitious project, “Blueprint for a Temple.” A soft-focus blue collage that measured more than 14 feet high, it transformed a few of her female friends into sculptural caryatids and melded the tile work of dilapidated New York tenements with the grandeur of ancient Greece.

Composed primarily of diazotypes, an inexpensive kind of photocopy typically used for architectural and technical drawings, the large piece was exhibited in 1980 at the now-defunct Alternative Museum in downtown New York.

Francesca’s parents, the artists George and Betty Woodman, donated “Blueprint for a Temple” in 2001 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it was displayed in a group show in 2012. There things stood until 2018, when an appraisal of the estate after the death of both her parents turned up an overlooked bag that contained 24 rolled-up diazotypes and four gelatin silver prints.

Unwrapping them in summer 2022, Lissa McClure, executive director of the Woodman Family Foundation, and Katarina Jerinic, collections curator, realized what they had discovered: “Blueprint for a Temple (II),” another version of Woodman’s crowning achievement. No one had thought to look for it because no one even knew that it existed. It was another mystery in a life that engendered more questions than answers.

Although George and Betty apparently believed otherwise, documentation confirms that the overlooked “Blueprint for a Temple (II),” not the work owned by the Met, is the piece displayed at the Alternative Museum. It is looser — less polished, more conceptual and experimental — than the previously known iteration. On one side of the taped and stapled diazotypes that constitute the temple, Woodman attached photographic prints and a hand-annotated diagram to reveal how the collage was made. At Gagosian, which has just begun representing the artist’s estate, “Blueprint for a Temple (II)” is accorded pride of place in the show “Francesca Woodman,” which also includes more than 50 lifetime prints.

For Woodman, “the temple,” as she casually called it, departed radically from the small black-and-white gelatin silver prints — largely depictions of her own body, often in the nude — that she had previously produced. “She wanted to get away from the intimate personal work,” McClure said in an interview. The diazotype collages opened a new door that her suicide, at age 22, slammed shut.

This is an auspicious time for Woodman. She is currently paired with Julia Margaret Cameron in an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London; and last year her reputation was burnished by the publication of a sumptuous facsimile edition of eight artist’s notebooks that she created by adding photographs and scrawled captions to 19th- and early-20th-century address books, ledgers and schoolbooks.

Like a comet, she burned out quickly and left behind a trail of posthumous appreciation. I am sometimes reminded of Edwin Mullhouse, the novelist protagonist of Steven Millhauser’s mock literary biography, who dies on his 11th birthday and is then subjected to intense critical scrutiny. What does it mean to categorize “periods” if an artist’s career spanned roughly six years and consisted in numerous instances of student assignments?

Although her early death arouses inevitable conjectures on what she might have achieved, Woodman in her brief life developed a distinct style and explored recurring themes. Playing off the centerpiece, the Gagosian show is organized to reveal one of the through lines: her preoccupation with the body as sculpture.

In the two “Blueprint for a Temple” collages, Woodman arranged diazotypes of female figures, who wear pleated dresses like the caryatids that support the entablature of the south porch of the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis in Athens. But as early as 1976, when Woodman was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, she already photographed her bare legs, as smooth and white as marble pillars, planted firmly on the pine board floor and juxtaposed with torn scraps of wallpaper. Perhaps around the same time in Providence, she depicted her nude body for a photographic triptych in an erect pose that resembles the one she later used in “Temple.”

During her junior year in Rome in 1977-8, surrounded by classical relics that she knew well from a childhood that was partly spent in Italy, she made a portrait of a friend wearing her polka-dot dress and standing straight as a column between two columns as she gazes up at a statue; and, once again in a museum, she photographed a nude body, probably her own, from behind, as she lies alongside a crumpled sheet on the floor beneath a plinth that might have once supported the fallen figure.

With the detached insouciance of a young person whose body is untouched by the ravages of time, Woodman romanticized decay. She said that she adopted diazotypes because they provided a cheap and quick way to make large prints and construct imposing pieces. (The two “Blueprints for a Temple” each measure more than 14 feet tall.) But it seems likely that she also was attracted to their fragility. Without modern-day conservation efforts to stabilize them, the diazotypes would have soon deteriorated in light.

The underlying conceit of the “Blueprint for a Temple” project stemmed from Woodman’s observation that the old bathrooms and hallways of the East Village apartments she saw in her last year in New York frequently featured Greek-key motifs in the tile floors and sculptural claw feet on the bathtubs. She wrote that she liked the “tension” between the image of the temple and the building blocks that derived from “the everyday banality of the bathroom.”

There is also a tension between the dreamy, blurry photographs that Woodman made and the tougher truths beneath them. Her salient predecessor is the French Surrealist photographer Claude Cahun, who made groundbreaking self-portraits in the period before World War II. A gender-shifting lesbian who might identify today as nonbinary, Cahun proclaimed, “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

It’s uncertain if Woodman even knew of Cahun. But like Cahun, she photographed herself, often in the nude, confined to corners and crammed into cupboards, dramatizing ways in which the human body, and particularly the female body, is placed and displaced. Both recognized and openly defied the conventions that restrain women in society, and both celebrated their (very different) sexualities with startling openness and distinctive flair. They combined the mundane with the mythic. Largely unknown in their lifetimes, today they are heralded as visionaries and venerated as cult figures.

Francesca Woodman

Through April 27, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, Manhattan; (212) 741-1111; gagosian.com.