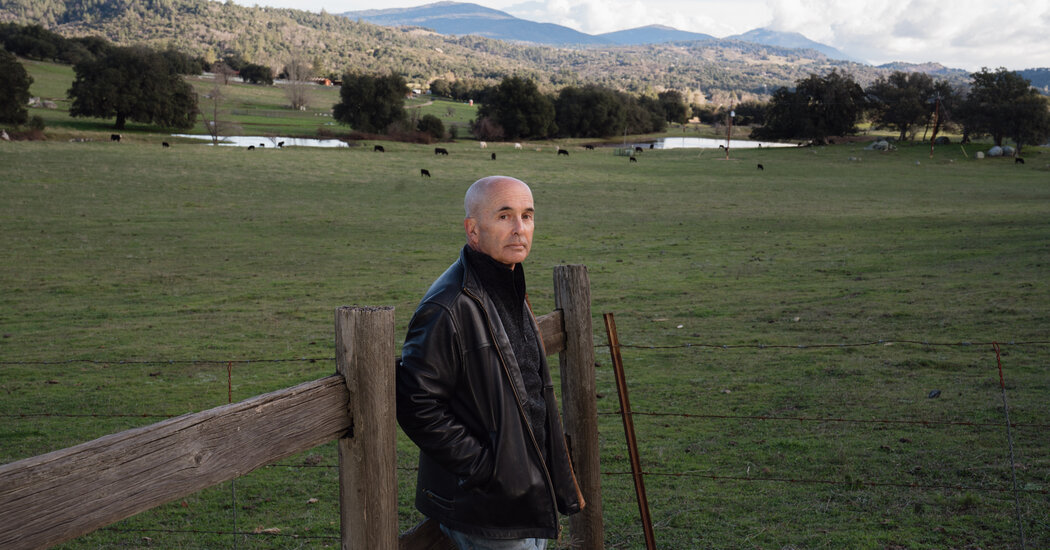

Like the cops, crooks and gangland toughs who populate his books, Don Winslow has something of a street fighter’s mentality.

Growing up in Rhode Island during the New England gang wars of the 1960s, local mafia types were part of the fabric of his childhood. After college, while working as a private investigator in New York City, one of his jobs was to act as bait for potential muggers — then fend for himself until a larger associate could step in, “hopefully before I got too beat up,” he said.

Winslow’s familiarity with the grittier side of life has served him well. Over a 33-year span he’s published more than 20 crime fiction novels, many of which have become best sellers or been adapted for film and TV.

Now, he’s turning his attention to “something that feels heavier,” he said. “City in Ruins,” the third book in Winslow’s sweeping Danny Ryan trilogy, which casts an Irish mobster as a modern-day Aeneas and draws inspiration from events that led to the Boston Irish Gang War, will be his last novel. He said he’s retiring from publishing in part so he can put more energy into political activism.

Since the 2020 presidential campaign, Winslow and Shane Salerno, a screenwriter, have together produced a series of highly combative videos and social media posts excoriating former President Donald Trump as, among other things, a “con man” and a “pathetic, broken little boy” (all told, the videos have received hundreds of millions of views.)

“There’s no way I can reach that many people with a novel,” Winslow said. “And the novels take so much time, in an era where really what is needed are much faster responses.”

Winslow spoke to The New York Times about “City in Ruins,” his activism and how it feels to turn the page on a three-decade career as a novelist. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What makes “City in Ruins” the one to end on?

I’ve been working on this trilogy for coming on 30 years. Of course I was doing other things, but I kept coming back to this. When I was getting close to finishing it, it was sort of this confluence of two rivers that come together. One was that this has been the work of a lifetime, and so finishing it felt like an end to things. These three books are a sort of homecoming for me, since I left Rhode Island when I was a teenager. The other stream is what’s been going on in the country since about 2015, and you can figure out the math of that — feeling more and more that what I should be doing is putting more energy into the fight against what I see as a neofascist movement in America led by a wannabe dictator.

Do you see a connection between your writing and your political work?

I think so. When I was rounding the turn on “The Cartel,” I started to get so angry about the war on drugs and it made me very political, which I never thought I’d be. I began to think that if I didn’t do something outside the world of narrative fiction, that I was just another guy making money off dope.

So, I thought I need to be speaking out. I’m not a big name, but whatever platform I had, I should be using. Around the time “The Cartel” came out I took out a full-page ad in The Washington Post advocating an end to the war on drugs. Later on I took out an ad in The New York Times attacking Trump and his attorney general for what they were doing in terms of criminalizing drugs. And then I started on social media and was surprised by the reaction.

What first drew you to crime fiction and what kept you there?

Crime fiction deals with humanity in extremis. It gets to the best and the worst of people. I also like it from a class perspective: particularly noir tends to be about the outcasts, the people who live in what Mr. Springsteen would call “the darkness on the edge of town.” But I think when I really look at it, it’s the beauty of the language. From the people who did it really well, the Raymond Chandlers of the world, the Elmore Leonards, the Lawrence Blocks, the MacDonalds — Ross and John D. — I came to age reading those people, and the beauty of the language still moves me.

Have you seen the genre change since you started?

I think it’s changed in a lot of ways and I think for the good. The tent has gotten bigger. It has opened up to where you can write quite realistic fiction, while there’s still room for murder-as-a-parlor-game. And also because it’s opened up demographically. Women have always been a major part of things — you can’t talk about the history of the genre without talking about Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie — but I think that women now are sort of dominating. And certainly ethnically and racially it’s become much more inclusive.

There’s been a relationship between crime fiction and film almost from the beginning of the genre. Why do you think that is?

I don’t think there’s another literary genre in which film is so intertwined to become almost inseparable. It’s visual, it’s emotional, it’s musical. I mean one of the great jazz albums of all time is Davis’s soundtrack for the French film “Ascenseur pour l’échafaud” (“Elevator to the Gallows”). So, I know when I sit down to write a book that it could end up going there. But I have to acknowledge that and forget it. Only bad things can happen. I’d end up writing a bad film treatment. People ask me all the time if I’m thinking of actors when I write. No, never.

Are you going to miss it?

I don’t feel fully retired yet, to be honest with you. I don’t know what it’s going to look like because the book is just coming out. But I’m a creature of routine — it’s terrible, man. I get up, I do the usual ablutions. I make a pot of coffee and then it’s five newspapers. I’ve done that forever. Then I would go to work on the books. What’s changed now is that now I’m spending more of my time on the newspapers.