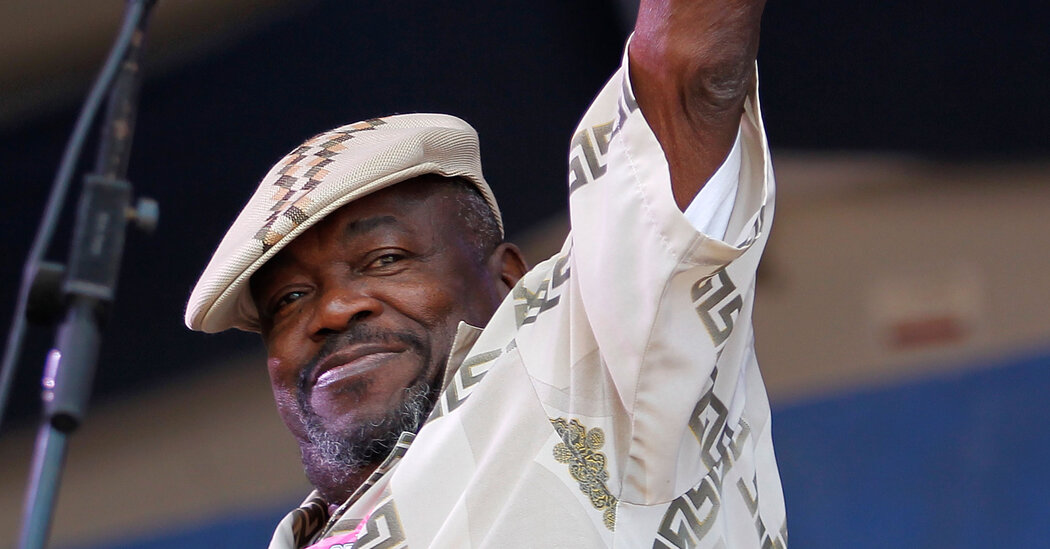

Clarence Henry, the New Orleans rhythm-and-blues mainstay who was known as Frogman — and best known for boasting in his durable 1956 hit, “Ain’t Got No Home,” that “I sing like a girl/ And I sing like a frog” — died on Sunday. He was 87.

The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, where Mr. Henry had been scheduled to perform this month, announced his death. The Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate reported that he died in New Orleans of complications following back surgery.

“Ain’t Got No Home,” which reached No. 30 on the Billboard Hot 100, became Mr. Henry’s signature hit and definitively captured his humor and his vocal high jinks. Written by Mr. Henry and released when he was a teenager, the song brought him his nickname and went on to become a perennial favorite on movie soundtracks, heard in “Forrest Gump,” “Diner,” “Casino” and other films. The Band opened “Moondog Matinee,” its 1973 album of rock ’n’ roll oldies, with “Ain’t Got No Home.”

The song was also used regularly in the 1990s by the right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh, who played it while mocking homeless people. Mr. Henry was grateful for the royalties.

His next hit — and his biggest one — arrived in 1961, when “(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do,” a song written by Bobby Charles and arranged by Allen Toussaint, reached No. 4. Later that year Mr. Henry had a No. 12 hit with his version of the standard “You Always Hurt the One You Love.” In 1964, the Beatles chose him as one of their opening acts for 18 shows on their American tour.

But pop trends left New Orleans R&B behind, and Mr. Henry returned to being a local hero — performing constantly in the clubs on Bourbon Street and appearing regularly at the annual Jazz & Heritage Festival.

Clarence Henry Jr. was born on March 19, 1937, in New Orleans, and grew up there and in nearby Algiers. His father was a railroad porter and an amateur musician who played stringed instruments and harmonica. His mother, Ernestine, managed the home.

Mr. Henry admired the New Orleans piano masters Fats Domino and Professor Longhair. “When I was about 8 years old, Momma sent my sister Lizzie for piano lessons, and she didn’t like it,” he was quoted as saying in Anthony P. Musso’s book “Setting the Record Straight” (2007). “I asked Momma to send me, and I told her that I’d show her what the 50 cents could do.”

He played trombone in his high school band, and he and some classmates joined a band, the Toppers, that backed the singer Bobby Mitchell. (Mr. Henry sometimes sang lead as well.) He went on to work in the saxophonist Eddie Smith’s band.

During one all-night gig, wishing the audience would go home, the 18-year-old Mr. Henry happened on a piano riff and started singing, “Ain’t got no home, no place to roam.”

He worked those words into a song that flaunted both his falsetto and a croaking technique — singing while inhaling — that he had used in high school to tease girls, as well as an “ooh-ooh” refrain. Paul Gayten, an A&R man at Chess Records who would share some songwriting credits with Mr. Henry, brought him to Argo Records, a Chess subsidiary, to record his first single.

“Troubles, Troubles” — a jovial-sounding song about contemplating suicide — was the single’s A-side, but a New Orleans disc jockey, Poppa Stoppa, decided to feature “Ain’t Got No Home” instead. When he started getting requests for “the frog song,” he took to referring to Mr. Henry as “the Frogman.” Mr. Henry, looking for something like Fats Domino’s moniker, “the Fat Man,” happily adopted it.

In the early 1960s, when his “(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do” was a hit both in the United States and in Britain, Mr. Henry toured England, where he met the Beatles. Their 1964 American tour made him an eyewitness to Beatlemania — including a New Orleans show at which hundreds of fans, mostly girls, stormed the stage. But it was the end of an era for New Orleans R&B.

“After the Beatles tour I went back to playing on Bourbon Street, and suddenly everything was guitars,” Mr. Henry told Offbeat magazine in 2004. “The Beatles put a hurt on us. It lasted a few years but we got it back.”

Mr. Henry continued to record through the 1960s, for Parrot, Dial, Roulette and other labels. But he resisted trends in rock and clung to what, in an interview for John Broven’s book “Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans” (1978), he called “the old-time music.”

He performed constantly on Bourbon Street until 1981 and in 1982 toured England, where he found an appreciative audience, stayed for a year and recorded an album, “The Legendary Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry,” that was released in 1983. In later years he performed less frequently, but over the years he appeared more than 40 times at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. He was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame and received a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm & Blues Foundation.

Mr. Henry, who lived for many years in Algiers, was married and divorced seven times — he married one of his wives twice — and had 10 children and 19 grandchildren. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

“As long as my health allows me to, I’m going to keep performing because it’s what I truly enjoy,” Mr. Henry told the New Orleans music historian Jeff Hannusch for his book “The Soul of New Orleans” (2001). “People want to see the Frogman, but you know the Frogman wants to see the people, too.”