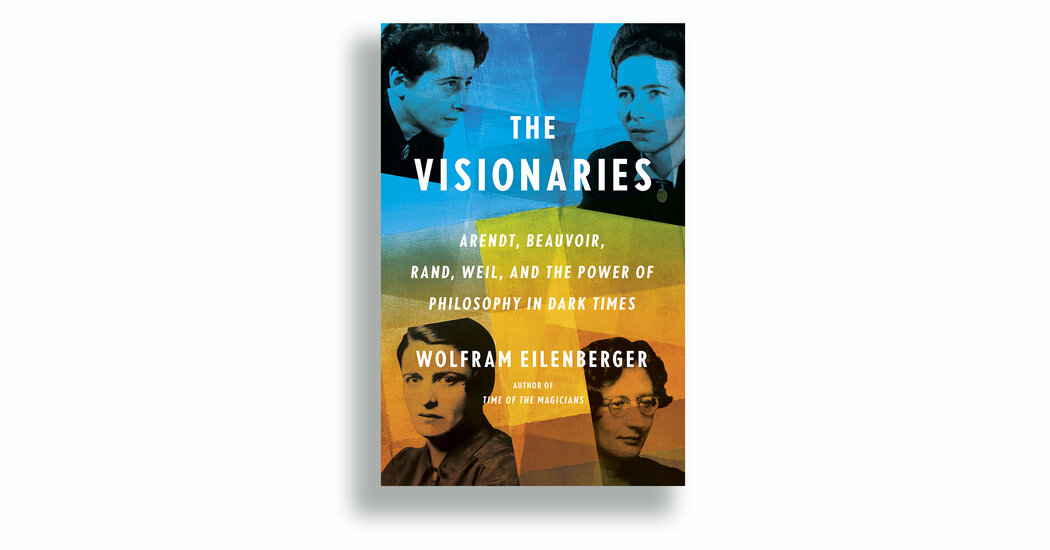

THE VISIONARIES: Arendt, Beauvoir, Rand, Weil, and the Power of Philosophy in Dark Times, by Wolfram Eilenberger. Translated by Shaun Whiteside.

If hell is other people, then so, too, is this world. Accepting the reality of others can take time. During a general strike in France in 1934, Simone de Beauvoir felt no particular urge to stand in solidarity with workers, including her colleagues at the lycée where she was teaching. “The existence of Otherness remained a danger to me,” she later recalled. “Around us other people circled, pleasant, odious or ridiculous: They had no eyes with which to observe me. I alone could see.”

It’s a quote that Wolfram Eilenberger uses to potent effect in “The Visionaries,” which traces the lives of four philosophers in the tumultuous decade before 1943. His previous book, the marvelous “Time of the Magicians,” was about Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Walter Benjamin and Ernst Cassirer in the decade after World War I; his new book, translated from the German by Shaun Whiteside, can be read as a sequel of sorts. The quartet this time is composed of four women, all in their 20s when the book begins in earnest, in 1933, their most productive years still ahead of them. Beauvoir, Simone Weil, Hannah Arendt and Ayn Rand: Each addressed the foundational question of the relationship between the self and others, between “I” and “we,” only to arrive at wildly different conclusions.

Their philosophical searching began, Eilenberger says, with an “honest bafflement that other people live as they do” — a feeling of separation, or estrangement, from the world. Beauvoir was teaching at the lycée in Rouen, having rejected the respectable life of marriage and family that her parents wanted for her; her main emotions at the time were boredom with her work and a general revulsion for the “bourgeois order.” Arendt, by contrast, was facing not boredom but terror; in May 1933, she was eating breakfast with her mother at a Berlin cafe when they were thrown into a car and interrogated by the Gestapo. After their release, they fled Nazi Germany and made their way to Paris.

Weil, also known as “Red Simone,” was horrified by Stalinism; she fell into arguments with her communist comrades, who were scandalized by her socialist insistence that “we should assign the highest value to the individual, not the collective.” And the Russian-born Rand, living in Hollywood and New York during the early years of the New Deal, was working on a novel about “the individual against the masses,” or what she called “the greatest problem of our century — for those who are willing to realize it.”