THE SUICIDE MUSEUM, by Ariel Dorfman

On Sept. 11, 1973, President Salvador Allende of Chile died inside the national palace in Santiago during a U.S.-backed military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet. Afterward, the Chilean army announced that suicide was the official cause of death, which many Chileans distrusted, if not flatly rejected. But in 1990, after 17 years of authoritarian rule in which any challenge to the junta’s line was dangerous, Pinochet lost power, and the nature of Allende’s death swiftly became a public question.

Was he assassinated? Did he die fighting, or choose death over capture? This is the mystery that powers “The Suicide Museum,” a new novel by the Chilean American author, playwright and activist Ariel Dorfman. It’s set mainly in 1990, during the thrilling, troubled months after Pinochet left, when Chile was starting to rebuild its democracy while still “crawling with criminals and accomplices and collaborators.” Its narrator, also a Chilean American author, playwright and activist named Ariel Dorfman, goes back to Santiago after years as a “man without a country,” dreaming of resuming his old life before the coup. But he’s got a secret mission, too.

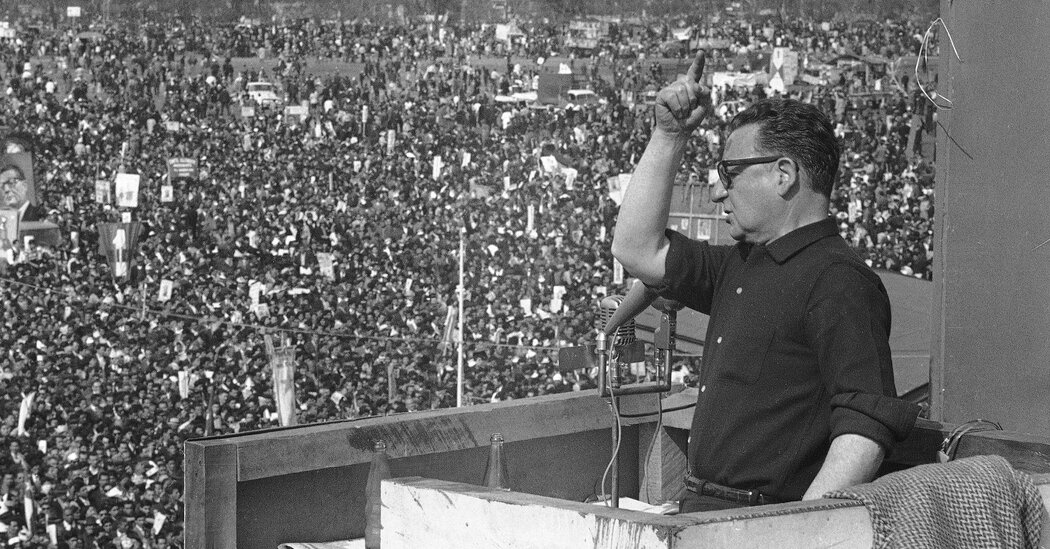

In 1983, while working against Pinochet from the United States, Ariel met an odd billionaire named Joseph Hortha. (For simplicity’s sake, I’ll refer to the author as Dorfman, and the character as Ariel.) Hortha, a Dutch Holocaust survivor and plastic-industry macher, worships Allende and what he stood for: the Chilean road to socialism, or “socialism through peaceful, electoral means.” He tells Ariel that, after his wife’s suicide in the late 1960s, only Allende’s inspiring presidential victory kept him from dying the same way. Hortha offers to pay Ariel a huge sum of money to return to Chile and figure out, “with utmost certainty, whether Salvador Allende killed himself. Whether his life was tragic or epic.”

For Ariel, even considering the possibility that Allende died by suicide isn’t easy. Like his creator, he was a member of Allende’s cabinet; he venerates the former president nearly as much as Hortha does. He is attached to an epic narrative in which Allende died fighting; any alternative theory “desecrated a sanctuary that was out-of-bounds.”