He had become the local expert on what he called the “unwanted side effects of old age,” so Dr. Bob Ross, 75, rubbed arthritis cream onto his hands and walked into an exam room to see his seventh elderly patient of the day. He had been a doctor in the remote town of Ortonville, Minn., for nearly five decades, caring for most of its 2,000 residents as he aged alongside them. He delivered their children, performed their high school physicals, tended to their workplace injuries and now specialized in treating the wide-ranging symptoms of what it meant to grow old in America.

“What’s hurting you most today?” he asked Nancy Scoblic, 79.

“Let me take out my list,” she said. “Sore knees. Bad lungs. I’ve got a spot on my leg and pain in my shoulder. Basically, if it doesn’t hurt now, it’ll probably hurt later.”

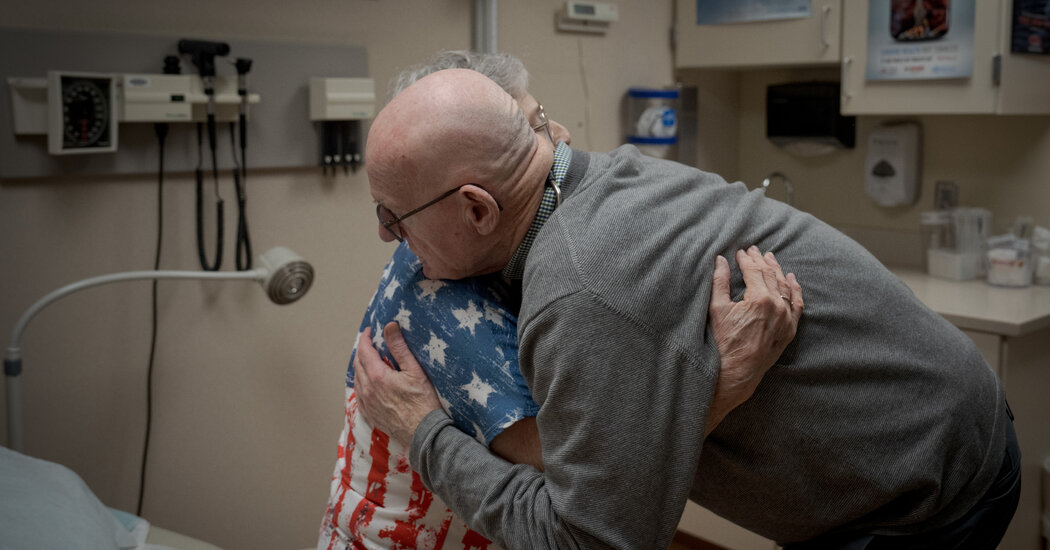

She’d known him for most of her life, first as Bobby, whom her family sometimes babysat, then as Bob in high school, and now as Dr. Bob — the physician who had cared for her grandparents and also her grandchildren, and who almost everyone in Ortonville entrusted with their most vulnerable moments. It was behind the closed door of Dr. Bob’s exam room where hundreds of people filled out their advance directives, took cognitive evaluations and tested out their new walkers and hearing aids. It was Dr. Bob who delivered bad news with a farmer’s directness and then sat with families around a hospice bed for hours when the only thing left to do was to pray.

Most of his patients were white, geriatric and still largely self-sufficient — members of the same demographic as the country’s two leading presidential candidates in the 2024 election, 81-year-old Joe Biden and 77-year-old Donald Trump. The conversations at the heart of an election cycle were the same ones unfolding inside Bob’s office: What were the best ways to slow the inevitable decline of the human body? How did aging impact cognition? When was it possible to defy age, and when was it necessary to make accommodations in terms of decision-making or professional routines? These were the questions he asked his patients each day, and also himself.

He took Nancy’s hand and helped her onto the exam table, checking for circulatory problems as he felt her lymph nodes and her carotid artery for signs of swelling. He pressed his hands against her abdomen to seek out masses in the liver or enlargement of the spleen. It was the same geriatric exam he conducted at least 25 times each week, as Ortonville’s soybean farmers aged into retirement and America’s baby boomers arrived in his office showing more evidence of cancer, more bruises from falls, more diabetes, more strokes and more signs of memory loss and possible dementia.

“You have a mildly elevated blood sugar that I want to keep an eye on,” Bob said. “If your body’s healthy, that helps keep your mind sharp.”

“What causes it?” Nancy asked. “What shouldn’t I eat?

“Carbs. Sugar. If it tastes good, spit it out,” he said. “But what helps most is exercise.”

“I can walk around the yard once or twice, but anything more than that and my breathing kicks in,” she said. “I’m probably about as good right now as I’m ever going to get.”

“That’s true for a lot of us,” Bob said.

Nancy sat on the exam table as he listened to her heartbeat, using an adaptive stethoscope he’d purchased a few years earlier when his own hearing started to decline. Lately, he could detect symptoms of his aging in the weakness that overwhelmed his hands during minor procedures, and in his occasional slip-ups with patients’ names, even when he could recall decades of their medical and personal histories.

Every few months, he gathered his medical partners to ask if they’d noticed any signs of his incompetence. “You have to promise you’ll be honest with me if you ever see something that worries you,” he told them. But even as he sometimes wondered if it was time to retire, his patients refused to let him.

“If I have to get old, then you have to keep taking care of me,” Nancy said. “I’ll be 80 this summer. Can you believe that?”

“If you’ve seen one person at 80, you’ve seen one person at 80,” Bob said. “There are a million different versions of growing old.”

Bob had already exceeded the average life expectancy at birth for an American man, 73 years, which was longer than he had expected to be alive. Both his parents died before 60, his mother from cancer while Bob was still in high school and his father from a heart attack a few years later. One of his brothers served 20 years in the Army and then was killed in a motorcycle crash; another, a smoker, died of lung cancer at age 74. Bob’s wife, Mary, had gone into premature labor in the 1980s with their twin boys, and one died in the hospital two days later. The other child survived and then thrived for 15 months until the following winter, when he developed croup, and Bob found him unresponsive in his crib late one night.

He’d witnessed and grieved enough death in his lifetime to believe that it was an immense privilege to grow old, and he planned to do whatever he could to preserve it.

His version of 75 meant starting each day by taking a half dozen medications to help treat his hypertension, diabetes, arthritis and high cholesterol. It meant diet shakes for lunch, a nap each afternoon and limiting himself to two smaller cans of Coke each day. It meant taping a handwritten note from his grandchildren onto his treadmill — “this helps keep papa in Beast Mode” — and spending an hour each night doing balance exercises, cardio and strength training. It meant taking bucket list trips with Mary to Norway and Africa, even if he had to travel with a sleep apnea machine. And it meant continuing to work five days a week in the clinic when the rest of the medical staff typically worked four, because caring for his aging patients gave him purpose and community, and lately they seemed to rely on him even more.

“I’ve started to forget basic words,” a 78-year-old patient told him one morning. “Elbow. Cheddar. Broccoli. One minute they’re here, and the next they’re gone. I run through all my kid’s names before I finally land on the right one.”

“How long should it take to go to the bathroom?” asked the next patient, 84. “I’ll finish the crossword puzzle, get through sports, still nothing. Is that normal?”

“One lap around Walmart and my feet are shot for a week,” said a 71-year-old.

“I don’t want to fall again in the shower, so I just do a spit bath,” said a 96-year-old.

“I wake up in the middle of the night and I’m out of breath like I just ran a marathon,” an 81-year-old said. “Is that normal? How could that possibly be normal?”

He had been trying to answer his patients’ questions and anticipate their needs since 1977, when he began working at Ortonville’s under-resourced hospital as one of two doctors in the entire county. He and Mary took out a second mortgage on their home to help start a foundation for the hospital, which it used to recruit a half-dozen doctors and build a state-of-the-art rural health care system. The nephew who once ran a lemonade stand in Bob’s front yard was now a doctor and the hospital’s chief executive; a student he mentored in high school had become his colleague as the first female physician in Big Stone County. He’d delivered more than 1,500 babies over the years, at least 100 of whom had grown up to work alongside him at the hospital. He’d started morning sports programs for children, run fitness classes for hospital employees and referred patients to a regular dementia support group that Mary helped start at the community library.

But lately during some of his appointments, he felt as if he had few solutions to offer. All he could do was listen to his patients’ concerns, empathize and explain the inevitable reality of what happened to an aging human body. The frontal cortex of the brain started to shrink over time, which led to slower recall, shortened attention spans and difficulty multitasking. Heart valves and arteries stiffened with age, which forced the heart to work harder and increased the likelihood of high blood pressure and heart attacks. Spinal disks flattened and then compressed. The metabolism slowed. Muscles contracted, skin bruised, bones weakened, teeth decayed, gums receded, hearing diminished, eyesight deteriorated — and it was normal. It was entirely and inescapably normal.

“I don’t like getting old either, but it sure beats the alternative,” Bob told one of his patients, Keith Kindelberger, 71.

“In terms of mind-set, I never have a bad day,” Keith said. “I think you’ve got me overmedicated.”

Bob laughed, and then checked Keith’s eyesight. “Attitude sure does count for a lot,” he said.

He took his lunch break and walked to the doctors’ lounge, turning the TV on to Fox News. He drank his diet shake and played solitaire on his iPad as Senator Mitch McConnell, 81, appeared on the screen to announce he would be stepping down as the Senate Republican leader in November after a recent fall and a few public memory lapses during news conferences.

“One of life’s most underappreciated talents is to know when it’s time to move on to the next chapter,” McConnell was saying, as Bob finished his shake and lay down for a nap.

He had considered retiring at least a half dozen times in the last decade, but he always chose to scale back instead. He stopped performing surgeries, taking call shifts, working in the emergency room and serving as county coroner. But he never wanted to quit seeing his patients, and sometimes he wondered if that was because of how much they needed him, or how much he needed them. “I’m not sure exactly who I’d be without that core piece of my identity,” he said one morning, as he went to visit the patient who knew him best.

His oldest brother, Jay Ross, was 83 years old and lived with his wife a few blocks from the hospital. Sometimes, Bob stopped by on his way to work to check his brother’s lungs or monitor his back pain, but now he handed Jay a cup of coffee and the daily crossword puzzle.

“I know these are supposed to be good for my mind, but sometimes I know the answer and I can’t recall the right word,” Jay said.

“I see that in myself, and in general that’s not a significant sign of dementia,” Bob told him. “Recall slows down. It happens to all of us as we age.”

“You’re not kidding,” Jay said. “Just look at our potential presidents.”

Jay was a Democrat, and Bob was a Republican. They had argued over politics for 60 years, but lately instead of debating policy positions they often found themselves studying the physical condition of the two candidates. Who, if anyone, was still fit for office? Who had a better chance of enduring the physical, emotional and mental rigors of another four-year term?

“In some ways, I look at it almost like evaluating a patient,” Bob said. According to the reports from President Biden’s most recent physical, he was experiencing neuropathy in both feet, sleep apnea, moderate to severe arthritis, a stiff gait from degenerative changes in his spine and an irregular heart rhythm that was under good control. His doctors had determined that he was in good mental health and didn’t need a cognitive exam, but in the last several months, he had confused the president of Egypt with the president of Mexico and stumbled up the stairs onto Air Force One.

At the same time, Donald J. Trump, 77, was overweight, partial to fast food, and often said he didn’t believe in exercise. Recently, he had seemingly referred to his wife, Melania, as “Mercedes.” Twenty-seven mental health professionals had come together to publish a book in 2017 about his mental state, called “The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump.”

“My preference would be that Joe’s gone, Trump’s gone and give us two new, viable options,” Bob said.

“It’s nice to finally agree,” Jay said.

He had been thinking back over his own life, trying to pinpoint the peak of his cognitive capabilities. He raised four children, taught advanced high school math, lived in Guam and New Zealand, wrote several books on local history, served on the school board and started a foundation, but now a few hours of conversation and a crossword puzzle could leave him fatigued.

“I think my peak was probably in my 40s or early 50s,” he told Bob. “That’s when I had the best combination of energy and experience. What about you?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Bob said. He no longer trusted his hands to perform a cesarean section, but in other ways he thought his experience was still making him a better and more empathetic doctor. “Probably 50s,” he said. “But it’s tough to admit the peak is behind you.”

“Then maybe it’s not,” Jay said. “It’s a very gradual decline.”

“Unless it’s a cliff,” Bob said.

What Bob feared was that one day he’d be sharp and the next his mind would begin to betray him, until eventually he stopped being himself altogether. He and Mary had read in a recent study that 1 in 7 people over age 71 could expect to have some type of dementia. By age 80, it was more like 1 in 4. Bob had noticed subtle behavioral changes in hundreds of his patients over the years, and the first step was always to administer a short test called the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which Trump had often bragged about “acing” in 2018, and which Biden’s staff said the president had no reason to take because “he passes a cognitive test at work every day.”

“Draw a clock,” one question read. “Put in all the numbers and set the time to 10 minutes after 11.”

“Name the maximum number of words in one minute starting with the letter F (normal < 11).”

“Tell me how an orange and a banana are alike.”

Usually it took less than 15 minutes for Bob’s patients to finish the test. When their scores indicated some mild cognitive impairment, he ordered an M.R.I. of the brain to rule out any treatable causes: previous strokes, thyroid malfunctions or diabetes-related complications. If all of that was negative, he braced himself for the conversation he dreaded most as a doctor. “I’m sorry, but we don’t have any good treatments or medications for negating the progress of this disease,” he’d told dozens of patients. Sometimes, all he could offer was a referral to the dementia support group that Mary hosted twice each month. So one morning about a dozen of Bob’s patients gathered in the Ortonville Public Library for a training session on caregiving as the disease progressed.

“Build a supportive connection, both verbally and physically,” the instructor said. “Let’s partner off and practice our initial greetings.”

Wayne Huselid, 73, stood up and helped his wife, Mary Jo, 70, out of her chair. It had been almost eight years since she scored below normal on a Montreal Cognitive Assessment and then went to see a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, where brain scans showed evidence of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Now she was staring at the wall behind Wayne and whispering in a stream of nonsensical syllables as he took her hand, introduced himself again to his wife of nearly 50 years and asked another question she could no longer answer. “Hi, sweetie,” he said. “It’s me. It’s Wayne. How are you today?”

How was she? It was the only question he had really cared about for the last several years, ever since he first suspected that something was wrong, in 2016. He was showing Mary Jo how to operate a simple piece of equipment on their farm outside of Clinton, Minn., but for some reason she couldn’t grasp it. She’d spent her life operating a combine harvester, managing the farm, running a grocery store and raising their children. He kept trying to instruct her for almost an hour before he lost his temper. Was she trying to be difficult? A few months later, she went for a drive and called him in tears because she couldn’t find her way back. He had spent three hours on the phone directing her, and he’d been a caretaker ever since.

“Make a positive statement about the person in the moment,” the instructor said.

Wayne rubbed Mary Jo’s fingers and looked into her eyes. “Your hands are so warm and soft,” he told her.

He was always in the process of losing her to dementia, day by day in a million little ways. Words. Shared memories. Even her physical self. As her symptoms worsened, he began attaching a location tracker to her clothing, but sometimes the signal didn’t work. One night they had gone to a doctor’s appointment and Mary Jo got out of the car without her coat. Wayne went into the back seat to grab it, but when he turned around a few seconds later she was gone. He searched all five floors of a nearby parking garage. He called the police. It was 15 degrees outside, and he ran through the neighborhood shouting a name she no longer recognized, until finally a police officer said he’d found a disoriented woman standing alone and crying near the train tracks.

“Focus on the skills that remain,” the presenter was saying. “Try not to dwell on the deficits.”

Wayne raised his hand. “See, that’s the part I struggle with,” he said. “Letting go of what’s gone. Are we just supposed to give up?”

“You have to treat the person they are, not the person that they were,” the instructor told him.

“But it’s like when I taught music at the high school,” Wayne said. “Say I had a kid in my class who was a problem. Do I write them off? Give up on their deficits? You try to figure out how to get through, right? If I can’t, that’s on me.”

That was what he felt sometimes with Mary Jo: that he wasn’t getting through, that he was failing her. When he laid her into bed each night, she had a distant look in her eyes that he interpreted as fear, or maybe loneliness. She stared at the ceiling while he held her hand, thinking back over his mistakes that day. Had he spoken too harshly? Had he gripped her hand a little too hard while he was putting on her glove?

“I guess Mr. Patience gets the better of me sometimes,” he told the instructor. “I should be able to handle more than I do.”

“Caretaking requires a lot,” the instructor said. “We need room to process and grieve.”

“But she’s still here,” Wayne said.

During his daily appointments, Bob often told his patients that they could either fear death or prepare for it, so he and Mary had spent the last few years making decisions and creating their own plan. They had figured out how to retrofit parts of their home, in case they would need ramps and wheelchairs. They’d chosen one son to make their end-of-life choices and another to manage their estate. Bob wanted to be cremated, but Mary planned to be buried.

“If I die first, you might need another companion,” she told him one night, as they sat down to eat. “That would be OK with me. You know that, right?”

“That’s a little morbid, for dinner,” he said.

“I like being aware of my mortality,” she said “There’s comfort in knowing what’s coming.”

“I get plenty of reminders,” Bob said. A few hours earlier, he’d signed a death certificate for another patient, a 91-year-old who had died at 3:40 a.m. “Manner of Death: Natural.” “Immediate cause: Alzheimer’s disease.” “Physician: Bob Ross.”

It was at least the 400th death certificate he had signed in the last decade, as Ortonville’s population continued to decline by attrition. When he was the county coroner, he had attended to all manner of violent and premature deaths: car crashes, suicides, frostbites, traumatic burns, firearm accidents, drownings, overdoses and at least two murders. But what he witnessed much more often were natural deaths, which didn’t always mean that they were uncomplicated, or easy.

Most of his patients died of renal failure, cancer, congestive heart failure, Alzheimer’s or kidney disease. He had cared for hundreds of patients in their final hours, when they lost the desire to eat or drink, their eyes turned glassy and their breathing became more labored. He held their hands and fingers as the skin became cold and mottled, a sign that the body was shutting down circulation to the extremities in order to preserve the brain and the heart for a few moments longer, in a last attempt to survive.

He sometimes gave patients morphine in those final minutes, as shallow breaths gave way to involuntary gasps, moans and rattles. He monitored the pulse as it slowed and finally stopped. The airway went silent, the body relaxed and there was something in the next moments that felt to him almost like peace. He wrote down the official time of death and prayed for his patients’ eternal rest.

“Our minds and our bodies aren’t built to last forever,” he told Mary. “There’s no use pretending otherwise. We all get our turn. We grow old and we die.”

“The evil days come and the years draw near,” Mary said, quoting what she remembered from one of their favorite Old Testament passages, Ecclesiastes 12.

“The sun and the light and the stars go dark,” Bob continued, and Mary nodded.

“The keepers of the house tremble,” she said, “and the mighty men stoop.”

Erin Schaff contributed reporting.