Table of Contents

The global climate summit’s declaration on fossil fuels got all the headlines this month in Dubai. But nature scored quite a win of its own.

In the final agreement, attendees of COP28 recognized that climate change threatens ecosystems and the billions of people who depend on them. They also committed to halting all deforestation and forest degradation by 2030, as well as the destruction of other land and marine ecosystems.

In a first, negotiators also aligned the climate declaration with a separate agreement to protect biodiversity that includes goals such as safeguarding 30 percent of the world’s land and seas.

“The ministers chose today to break from traditional silos and to pursue strategies that put nature at the heart of climate change responses,” Joe Walston, the executive vice president of Wildlife Conservation Society, said in a statement.

Nature can be harnessed in the struggle to curb global warming and its most tragic effects in myriad ways: Forests store carbon and reduce temperatures, coral reefs help shield coasts from extreme weather, and grasslands safeguard water sources from droughts.

But to fully protect various ecosystems and help them combat climate change, we have to understand them — and there’s a lot to figure out. For example, scientists estimate that a staggering 91 percent of ocean species have yet to be classified, and 80 percent of the oceans remain unmapped.

Some help from space

One piece of the puzzle is coming into focus: how much carbon ecosystems are actually storing.

Scientists are now using space-based lasers to gauge the biomass of forests all around the world, which lets them calculate how much planet-warming carbon the trees are keeping out of Earth’s atmosphere. NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (or GEDI, pronounced like the order of knights in “Star Wars”) deployed a sensor on the International Space Station in 2018.

Data from that project is now being analyzed, with surprising results: Forests hold, on average, about 30 percent more carbon than what countries have previously reported. Keeping those forests healthy, and preventing their massive stores of carbon from being released into the atmosphere, is even more crucial than we thought.

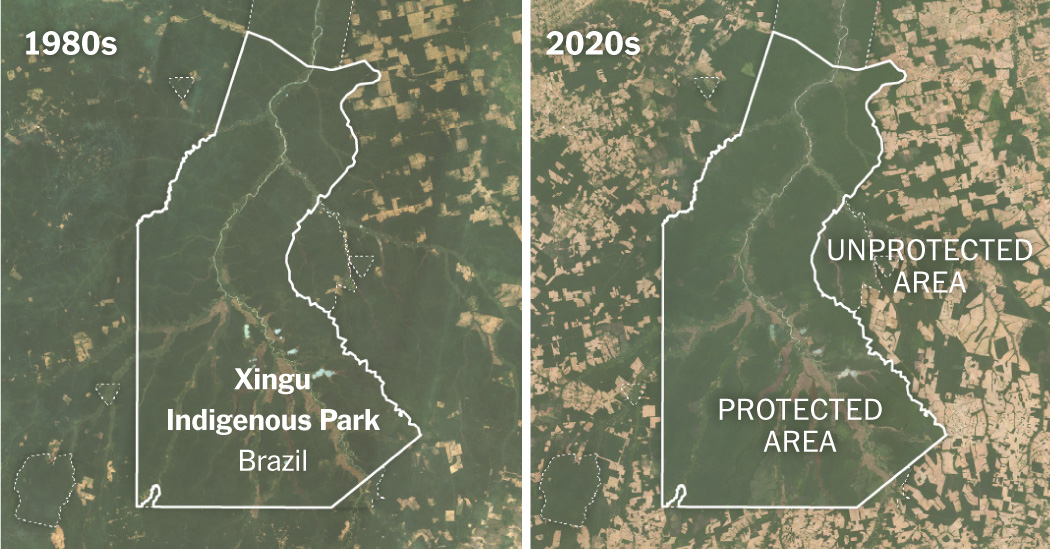

Over the last century, governments around the world have drawn boundaries to shield thousands of the world’s most valuable ecosystems from destruction, from the forests of Borneo and the Amazon to the savannas of Africa.

These protected areas have offered lifelines to species threatened with extinction, supported the ways of life for many traditional communities and safeguarded the water supplies of cities. But reserves are facing increasing pressure, their boundaries largely disregarded as people cut down trees and push deeper into the ecosystems set aside for protection.

A study based on GEDI data found that, in the last two decades, designating protected areas to prevent deforestation has prevented the release of about a year’s worth of fossil fuel emissions.

“It’s lots of carbon, more carbon than we expected,” said Laura Duncanson, a remote sensing scientist at the University of Maryland and a co-author of the study. She called the findings “a beautiful side benefit” of global forest conservation.

What “simply can’t be replaced”

Political and economic pressure to get rid of reserves is growing, and keeping them safe is becoming harder.

“We’ve got to focus on conserving the critical ecosystems, the irrecoverable carbon stocks that simply can’t be replaced,” said Zoe Quiroz-Cullen, a director at Fauna & Flora, an international wildlife nonprofit.

A 400-year-old tree that is cut down holds a lot more carbon than one of the same species that is planted today.

With the new declaration out of Dubai, nearly 200 countries are now committed to ending deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. But Quiroz-Cullen told me that the world still needed a more specific agreement with targets, paths of action and, perhaps most important, funding streams.

Still, the recognition that fossil fuels are the problem and nature is part of the solution was a victory. Nature’s ability to help us, though, will depend on how much we can protect it.

“It’s all linked up with nature,” Quiroz-Cullen said. “The more we erode it and the more climate change we incur, the more difficult it is for nature to do its job.”

California’s fight to fix its water crisis

The story of California’s water wars begins, as so many stories do in the Golden State, with gold.

The prospectors who raced westward after 1848 scoured fortunes out of mountainsides using water whisked, manically and in giant quantities, out of rivers. Early water laws enshrined a frontier principle: first come first served.

Subsequent settlers gobbled up land and laid down dams, ditches and communities. Shrewd barons turned huge estates into jackpots of grain, cattle, vegetables and citrus. California grew and grew and grew, sprouting new engines of wealth along the way: oil, Hollywood, Apple, A.I.

Today, the state is at the mercy of claims to water that were staked more than a century ago, in a cooler, less crowded world. As drought and overuse sap the state’s streams and aquifers, California finds itself haunted by promises made to generations of farmers and ranchers that they would have priority access to the West’s most precious resource with scant oversight, essentially forever.

A Times analysis found that decades of unrestricted groundwater pumping has left many aquifers in severe decline.

To address this most 21st century of crises, a state that prides itself on creating the future is first reckoning with its past.

“The reality is that California had a pretty soft touch in water rights administration” compared with many Western states, said E. Joaquin Esquivel, the chair of the state’s water board. “The system worked for as long as it really could.” — Raymond Zhong